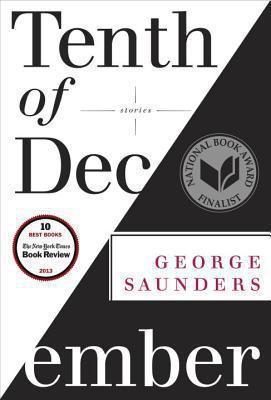

Tenth of December : stories

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Community Centre | Available |

| Community Centre | Available |

| Victoria | Available |

Browse Related Items

| Genre |

| Fiction. |

- ISBN: 0812993802

- ISBN: 9780812993806

- Physical Description 251 pages

- Edition 1st ed.

- Publisher New York : Random House, [2013]

- Copyright ©2013

Content descriptions

| Formatted Contents Note: | Victory lap -- Sticks -- Puppy -- Escape from Spiderhead -- Exhortation -- Al Roosten -- The Semplica Girl diaries -- Home -- My chivalric fiasco -- Tenth of December. |

| Immediate Source of Acquisition Note: | LSC 29.95 |

Additional Information

New York Times Review

Tenth of December : Stories

New York Times

February 3, 2013

Copyright (c) The New York Times Company

"WRITING short stories is very hard work." That, at any rate, is what George Saunders had to say on the subject some years ago, in an essay about the postmodern master Donald Barthelme, and lest anyone raise a skeptical eyebrow - since by then Saunders had already proved himself to be one of the most gifted, wickedly entertaining story writers around - he continued to wring his hands, revealingly, a few pages later: "The land of the short story," he fretted, "is a brutal land, a land very similar, in its strictness, to the land of the joke." I love how this makes Saunders sound like a nervous explorer, crossing thin ice to reach a distant smoldering volcano. The land of the short story! But it also captures something fundamental about his own brutal, jokey stories, which for all of their linguistic invention and anarchic glee are held together by a strict understanding of the form and its requirements. Take plot. In "Tenth of December," his fourth and best collection, readers will encounter an abduction, a rape, a chemically induced suicide, the suppressed rage of a milquetoast or two, a veteran's post-traumatic impulse to burn down his mother's house - all of it buffeted by gusts of such merriment and tender regard and daffy good cheer that you realize only in retrospect how dark these morality tales really are. And "Tenth of December" is very dark indeed, particularly in its consideration of class and power. It's been seven years since Saunders's last collection, "In Persuasion Nation," and in the interim America has settled into a state of uncertain financial gloom that seeps into these stories like smoke beneath a door. Money worries have always figured in Saunders's work, but in "Tenth of December" they cast longer shadows; they have deepened into a pervasive, somber mood that weights the book with a new and welcome gravity. Class anxiety is everywhere here. In "Puppy," a woman whose marriage has lifted her from dysfunctional roots is so horrified by a poor family's squalor that she finds empathy impossible, with tragic results. In "Home," a soldier returning from the Middle East drops in unannounced on his ex-wife and her much richer new husband: "Three cars for two grown-ups, I thought. What a country." In "The Semplica Girl Diaries," a father broods that he can't provide his children with the same luxuries their classmates have: "Lord, give us more. Give us enough." Elsewhere he confides to his journal that he does "not really like rich people, as they make us poor people feel dopey and inadequate. Not that we are poor. I would say we are middle. We are very very lucky. I know that. But still, it is not right that rich people make us middle people feel dopey and inadequate." (What identifies this as a George Saunders story, and not, say, a Raymond Carver one, is its deadpan science fiction gloss: the luxuries in question are third-world women strung up as bourgeois lawn ornaments.) Yet despite the dirty surrealism and cleareyed despair, "Tenth of December" never succumbs to depression. That's partly because of Saunders's relentless humor; detractors may wonder if they made a wrong turn and ended up in the land of the joke after all. But more substantially it's because of his exhilarating attention to language and his beatific generosity of spirit. "Every human is born of man and woman," one narrator reflects, in what sounds suspiciously like an artist's statement. "Every human, at birth, is, or at least has the potential to be, beloved of his/her mother/father. Thus every human is worthy of love. As I watched Heather suffer, a great tenderness suffused my body, a tenderness hard to distinguish from a sort of vast existential nausea; to wit, why are such beautiful beloved vessels made slaves to so much pain?" This "vast existential nausea" is Saunders in a nutshell. Yet he subverts and mocks his own humanist idealism both by presenting it as the product of a drugged mind - the narrator here is a prisoner, medicated against his will to become more eloquent - and by having a lab assistant gently deflate it a few paragraphs later: "That's all just pretty much basic human feeling right there." Fans of Saunders's three earlier collections, beginning with "CivilWarLand in Bad Decline" in 1996, will immediately recognize the gonzo ventriloquism that gives his work such comic energy. By tapping into the running interior monologues of his hopeful, fragile characters, Saunders creates a signature voice that's simultaneously baroque and demotic - a trick he pulls off by recognizing just how florid our ordinary thoughts can be, how grandiose and delusional and self-serving: "Did she consider herself special?" a teenage girl asks in "Victory Lap." "Oh, gosh, she didn't know. In the history of the world, many had been more special than her. Helen Keller had been awesome; Mother Teresa was amazing." This is Alison Pope, age 14, who speaks to herself in beginner's French and entertains innocent fairy tale fantasies of meeting a boy she thinks of, generically, as "special one." Instead, she's abducted by a would-be rapist with romantic delusions of his own: "In Bible days a king might ride through a field and go: That one. And she would be brought unto him. . . . Was she, that first night, digging it? Probably not. Was she shaking like a leaf? Didn't matter." IF a damsel-in-distress narrative seems a creaky vehicle for Saunders's spirited wordplay and high moral inquiry, well, it's true there's nothing especially sophisticated about his story lines; up close, his volcanoes turn out to be fizzing with baking soda and vinegar. And his brand of straightforward dramatic irony - we see the delusions the characters don't - tends to put the reader (and the author) in an uncomfortably superior position; at his worst Saunders can come off as a little smug or complacent, like somebody with a bumper sticker reading "Mean People Stink." But beneath the caricatures his best stories are animated by true fellow feeling and an anthropologist's cool eye for the quirks of human behavior: a boy in an Indian headdress, racing down a school hallway; a wife's fond memory of "that laugh/snort thing" her husband does in her hair; the patriotic piety that leads everybody the veteran meets to thank him for his service. Saunders hears America singing, and he knows it's ridiculous, and he loves it all. The title story, which closes the volume, is in many respects a companion piece to "Victory Lap," which opens it. Another dreamy adolescent is lost in fantasy until physical danger intrudes, this time in the form of actual thin ice. The story ends on a hopeful note, as so many of the stories here do - this book, with its cover divided neatly into black and white like a semaphore yin-yang symbol, is at least as interested in human kindness as it is in cruelty. It's no accident, I think, that Saunders has chosen to set the story on this particular day, or to name the collection as a whole after it. Why the 10th of December? It's not the solstice yet; the days are drawing shorter, but things aren't as dark as they could be; even now, there's still a glimmer of light. 'Every human is worthy of love,' one character thinks, in what sounds suspiciously like an artist's statement. Gregory Cowles is an editor at the Book Review.

Publishers Weekly Review

Tenth of December : Stories

Publishers Weekly

(c) Copyright PWxyz, LLC. All rights reserved

The title of Saunders's fourth collection doesn't reference any regularly observed holiday, but for the MacArthur-certified genius's fans, a new collection, his first in six years, is a cause to celebrate. Yet the 10 stories here-six of which ran in the New Yorker-might make readers won over by earlier, irony-laced absurdities like Pastoralia's "Sea Oak" or corporate nightmares like "CommComm" from In Persuasion Nation question whether they know Saunders as well as they think they do. Yes, "Puppy" is about a maniacally upbeat mother on a "Family Mission" to adopt a dog only to discover the dog owner's son chained to a tree in the backyard "via some sort of doohicky." Yes, "Escape from Spiderhead" is about evil experiments to make love and take love away using drugs with names like DarkenfloxxT. But readers expecting zany escapism will be humbled by the pathos on display in stories like "Home," where a soldier returns to his humble origins. "Victory Lap" features a disarming case of child kidnapping, and "The Semplica Girl Diaries" is a heartbreaking chronicle of two months of changeable fortune in the life of a lower-middle-class paterfamilias of modest expectation ("graduate college, win Pam, get job, make babies, forget feeling of special destiny"). Eventually, a suspicion creeps in that, behind Saunders's comic talents, he might be the most compassionate writer working today. Agent: Esther Newberg, ICM. (Jan. 8) (c) Copyright PWxyz, LLC. All rights reserved.

BookList Review

Tenth of December : Stories

Booklist

From Booklist, Copyright (c) American Library Association. Used with permission.

*Starred Review* Saunders, a self-identified disciple of Twain and Vonnegut, is hailed for the topsy-turvy, gouging satire in his three previous, keenly inventive short story collections. In the fourth, he dials the bizarreness down a notch to tune into the fantasies of his beleaguered characters, ambushing readers with waves of intense, unforeseen emotion. Saunders drills down to secret aquifers of anger beneath ordinary family life as he portrays parents anxious to defang their children but also to be better, more loving parents than their own. The title story is an absolute heart-wringer, as a pudgy, misfit boy on an imaginary mission meets up with a dying man on a frozen pond. In Victory Lap, a young-teen ballerina is princess-happy until calamity strikes, an emergency that liberates her tyrannized neighbor, Kyle, the palest kid in all the land. In Home, family friction and financial crises combine with the trauma of a court-martialed Iraq War veteran, to whom foe and ally alike murmur inanely, Thank you for your service. Saunders doesn't neglect his gift for surreal situations. There are the inmates subjected to sadistic neurological drug experiments in Escape from Spiderhead and the living lawn ornaments in The Semplica Girl Diaries. These are unpredictable, stealthily funny, and complexly affecting stories of ludicrousness, fear, and rescue.--Seaman, Donna Copyright 2010 Booklist

Kirkus Review

Tenth of December : Stories

Kirkus Reviews

Copyright (c) Kirkus Reviews, used with permission.

A new story collection from the most playful postmodernist since Donald Barthelme, with narratives that can be enjoyed on a number of different levels. Literature that takes the sort of chances that Saunders does is rarely as much fun as his is. Even when he is subverting convention, letting the reader know throughout that there is an authorial presence pulling the strings, that these characters and their lives don't exist beyond words, he seduces the reader with his warmth, humor and storytelling command. And these are very much stories of these times, filled with economic struggles and class envy, with war and its effects, with drugs that serve as a substitute for deeper emotions (like love) and perhaps a cure (at least temporary) for what one of the stories calls "a sort of vast existential nausea." On the surface, many of these stories are genre exercises. "Escape from Spiderhead" has all the trappings of science fiction, yet culminates in a profound meditation on free will and personal responsibility. One story is cast as a manager's memo; another takes the form of a very strange diary. Perhaps the funniest and potentially the grimmest is "Home," which is sort of a Raymond Carver working-class gothic send-up. A veteran returns home from war, likely suffering from post-traumatic stress. His foulmouthed mother and her new boyfriend are on the verge of eviction. His wife and family are now shacking up with a new guy. His sister has crossed the class divide. Things aren't likely to end well. The opening story, "Victory Lap," conjures a provisional, conditional reality, based on choices of the author and his characters. "Is life fun or scary?" it asks. "Are people good or bad?" The closing title story, the most ambitious here, has already been anthologized in a couple of "best of" annuals: It moves between the consciousness of a young boy and an older man, who develop a lifesaving relationship. Nobody writes quite like Saunders.]] Copyright Kirkus Reviews, used with permission.