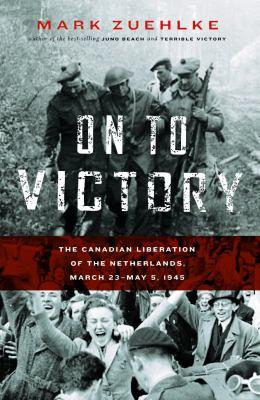

On to victory : the Canadian liberation of the Netherlands, March 23-May 5, 1945

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Victoria | Available |

Browse Related Items

- ISBN: 1553654307

- ISBN: 9781553654308

-

Physical Description

print

525 pages : illustrations, maps. - Publisher Vancouver : Douglas & McIntyre, [2010]

- Copyright ©2010

Content descriptions

| Bibliography, etc. Note: | Includes bibliographical references (pages 451-507) and index. |

| Immediate Source of Acquisition Note: | LSC 35.00 |

Series

Additional Information

On to Victory : The Canadian Liberation of the Netherlands, March 23-May 5 1945

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

On to Victory : The Canadian Liberation of the Netherlands, March 23-May 5 1945

Introduction: The Sweetest of Springs Amsterdam, May 7, 1945 Less than forty-eight hours after the ceasefire in the Netherlands and northwest Germany had been formally declared, the Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry had set out on an urgent mission. Crammed into trucks, Bren carriers, and jeeps, the troops had left Amersfoort at 0805 hours with orders to follow a westward route through Hilversum and Amsterdam to reach Haarlem and the small village of Bloemendaal on the city's outskirts. Here were reportedly large ammunition dumps and weapons caches that needed immediate securing. Also in the area of Haarlem were innumerable thousands of German troops waiting to surrender and be readied for a forthcoming return to their homeland. The war was over, administrating the peace a matter now of pressing necessity. PPCLI commander Lieutenant Colonel R.P. "Slug" Clark had raced ahead of his men to contact the German commanders at Haarlem and prepare for an orderly takeover by the Canadians. Soon after his dawn departure, Clark and the two men riding in his jeep anxiously approached a roadblock that was part of the still heavily manned Grebbe defensive line. The large number of "fully armed" Germans manning it "seemed to be extremely surprised to see an Allied vehicle passing through their fortification," Clark later reported, but they did nothing threatening and the little party dashed on. As they entered Amsterdam "early in the morning, the city appeared to be deserted," until a couple of people appeared and "suddenly recognized an Allied vehicle. There were a few shouts, then heads began to pop out of windows. Before we got to the end of this long main street it seemed as though the whole population of the city was blocking our pathâ¦From all appearances no Allied soldiers had been along this main road from the south until my small party arrived," Clark wrote. He would thereafter claim that the PPCLI "was the first Allied force to enter Amsterdam" and confirm its liberation. By the time the PPCLI main body arrived a couple of hours later, Amsterdam was ready. "The reception by the civilians was overwhelming," the battalion's war diarist wrote. "Vehicles were completely covered with flowers--thousands of people lined the streets screaming welcomes, throwing flowers, confetti and streamers, waving flags and orange pennants, and boarding vehicles. Never have so many happy people been seen at one time." The same story had played out during the approach to Amsterdam, just as was happening in almost every part of the Netherlands--particularly in the large cities in the Randstadt region, which encompassed not only Amsterdam but also Rotterdam, the Hague, Leiden, Haarlem, Hilversum, and Utrecht. This was the liberation. This was the time that the Dutch would forever after remember as "the sweetest of springs." For the Canadians, it was a cause of bewilderment. "Every village, street and house was bedecked with the red, white and blue Dutch flags and orange streamers, which in the brilliant sunlight made a gay scene," one PPCLI officer wrote. "The Dutch people lined the roads and streets in thousands to give us a great welcome. Wherever the convoy had to slow up for a road block or a bridge, hundreds of people waved, shouted and even fondled the vehicles. When the convoy reached the outskirts of Amsterdam it lost all semblance of a military column. A vehicle would be unable to move because of civilians surrounding it, climbing on it, throwing flowers, bestowing handshakes, hugs and kisses. One could not see the vehicle or trailer for legs, arms, heads and bodies draped all over it...Boy scouts as well as civilian police and resistance fighters had turned out in large numbers to attempt to control the crowds and to guide the vehicles to their destinations. "The Dutch people whom we saw looked healthier than we expected to find them but most of them had sunken eyes betraying months of insufficient food. It was said that there were many thousands in Amsterdam not out to welcome us because they were too feeble from hunger to move into the streets." In the late morning, a second column of Canadian troops wended its way through the Amsterdam crowds. This was another battalion of the 1st Canadian Infantry Division's 2nd Brigade--the Seaforth Highlanders of Canada with a squadron of Princess Louise's Dragoon Guards armoured cars rumbling along in support. About a thousand men were tasked to formally garrison the capital city with its nearly 800,000 people. Lieutenant Colonel Henry "Budge" Bell-Irving thought "there must have been half a million people throwing beautiful flowers at us. An old lady, handing me a bunch of roses, said from the very bottom of her soul, 'Thank God, at last you've come.'" "Thousands upon thousands line the streets for four miles," Seaforth's Padre Roy Durnford scribbled in his diary that evening. "Flowers--roses, tulips & every sort. Crowds load every vehicle including our RAP [Regimental Aid Post] jeep. I stand on running board. Terrific welcome. They tell in broken English with tears & unbridled joy how thankful they are to us. Children are lovely. Terrible shortage of food, ½ loaf bread, handful of potatoes per week. No fats, no tea, sugar, cocoa, firewood. Thousands of old people die. We camp in parkâ¦.I rejoice today with the free." Vondelspark provided a semblance of refuge where the vehicles could be parked and barriers erected to keep most of the crowds surrounding the Canadians at bay. Much earlier, to prevent its trees from being cut down for firewood during the hard winter months, the park had been placed off limits by the German occupying forces and Dutch city officials. In the city's heart, it provided an ideal location for a small army camp. Here, the small Canadian force hunkered, knowing it had little or no control over a city that thronged not only with Dutch civilians but also with still armed German soldiers. But the encampment was still easily infiltrated. Young Margriet Blaisse's family home's garden bordered the park, and a small gate in the backyard fence provided easy access. From their home, the Blaisse family saw the jeeps, trucks, and soldiers. Turning to Margriet, her father said, "Look, dear, I think the Canadians are in the park. Go over and see if you can talk to one of them." Margriet readily agreed. As she headed off, her father called out, "Whatever you do, don't fall in love with any of them. They're all going back to Canada and you're staying right here in Amsterdam!" The first Canadian Margriet saw was a tall, slender man. She walked up boldly. "My parents would be thrilled if you could come to the house, so we can thank you for the liberation. We live right here in the park." Lieutenant Wilf Gildersleeve smiled, introduced himself, and then called to his platoon. "Hey, fellas, we're going to have a drink or something." "I came back with twenty Canadians," Margriet said later. "My parents couldn't believe it. They were all sitting on the balcony laughing, crying, and talking, and the whole bit. Then they left again. In the evening, we still had no electricity, no light, no bell. We heard knocking on the front door. So my mother said to me, 'Go and see who's knocking.' "I went downstairs, opened the door, and there was Wilf with a friend. Wilf was dressed in a kilt with his arms full of bread and butter and cheese and ham, and I yelled back to my mother, 'Two men in skirts,' because I had never seen a fellow in a kilt before. They came in and they watched us eat. Oh my gosh, we ate so much that evening." Rotterdam, May 7, 1945 In their best clothes and with hair as neatly styled as possible, twenty-one-year-old Wilhelmina Klaverdijk and her younger sister by two years walked downtown. Rumours were rife that the Canadians had come. Approaching the immense Lever Brothers factory they saw a column of large military trucks grinding along the approaching road and crowding one after the other into the sprawling factory parking lot. As the trucks came to a halt, soldiers poured out and formed into ragged groups. Until now, the only soldiers Wilhelmina had ever seen had all been Germans, who wore fine uniforms and seemed well built. In their rumpled and stained khaki, the Canadians looked shabby by comparison. But they were the liberators, the men who had brought freedom to Rotterdam and the rest of the Netherlands. "See all those soldiers there," Wilhelmina declared to her sister, "I'm going to kiss all these guys." She strode right into their midst without a backward glance and put her arms around the first soldier she met. "Thank you for liberating me," she said, and gave the surprised fellow a big kiss. Wilhelmina was not alone. Hundreds of young women were descending in throngs on the parking lot and the soldiers there. "We kissed so many soldiers that day," she later said. "We did it all that day and the next." Nijmegen, May 7, 1945 At 1st Canadian General Hospital in Nijmegen, the acting principal matron, Lieutenant Evelyn Pepper, and most of the hospital staff had initially found it difficult to believe the ceasefire announcement that had been issued throughout the Netherlands, Denmark, and north Germany on the evening of May 4. "Exultation among the nursing staff was slightly delayed," Pepper remembered. So they had watched with a sense of bemusement as the "people in Nijmegen flooded into the streets dancing and singing and making huge bonfires. They were burning the blackout windows they didn't need anymore. Their doors were opened wide for Canadians to come in and join the celebration. Some of our boys certainly enjoyed the invitation." As for the nurses, however, they "could not believe that the message was true. Casualties were still coming to the hospital. Our hospital was well filled. We were all very busy. In retrospect, we were probably in a mild shock. Our thinking cleared, however, on May 7 when a Cease Fire affecting all troops in Europe was issued and VE-Day announced, on May 8, 1945 by Prime Minister Winston Churchill. The long stream of battle casualties had been finally ended. As we celebrated that night, a deep sense of relief and quiet thankfulness stirred in our hearts. The war in Europe was over." North of Oldenburg, Germany, May 7, 1945 "There are no boisterous victory celebrations on this north German plain. It is enough to relish the deep relief and gratitude that the fighting is over and that you have survived," Captain George Blackburn of the 4th Canadian Field Regiment wrote. "There is an unreal, aimless quality to these first few days." Before the ceasefire was announced late on May 4 and the Canadian units operating in Germany ordered to stand down, most had been in the midst of readying to put in renewed attacks toward Wilhelmshaven--the large enemy naval base. Major George Cassidy, commanding 'D' Company of the 4th Canadian Armoured Division's Algonquin Regiment, had been teeing up an offensive that would see them supporting a troop of tanks in a night attack against some woods believed held by German troops. Rumours had been swirling around that an armistice was imminent, and the last thing Cassidy had wanted to do was commit his men to an attack in those circumstances. As he walked up to his company's Bren carrier, a signaller advised that a message had just come in for him. Using "the dim dash bulb light of the carrier" to read by, Cassidy glanced at the paper and "the words seemed to dance before" his eyes: 'Stand down. All offensive action will cease until further notice.' "Down the road, the tanks, motors rumbling throatily, were crowded with men waiting to ride up to a battle that was not to come off. How appropriate to walk down the column in the gathering darkness and to give, with more meaning than it ever had before the old 'washout' signal. 'Climb down, lads. It's all over. All over.' "Cheers? None. Emotion? Not visible, at any rate. In a few moments the tanks were churning off the road into a laager, the men were digging in in a soggy field of rich, black earth. In the distance the guns of our artillery were still growling away. Here there was no sound but the clink of the shovels, the soft murmurs of voices. Stealthily, gently the rain began to fall again." That same morning, in a cold drizzle, 3rd Canadian Infantry Division's Highland Light Infantry (HLI) had carried out an assault crossing by boats of a German canal southwest of Timmel. Meeting only token resistance, the battalion was quickly on the march toward the objective town of West Grosse. Those few Germans encountered proved all too ready to lay down arms and surrender. The troops had just entered West Grosse unopposed at 1720 hours when a radio signal was received from brigade. "Firm up your present area, accept no casualties, and do not engage in any unnecessary action. Do not use artillery if it can be avoided." Three hours later, battalion headquarters learned by the BBC radio broadcast that "all German forces in North West Germany, Holland, and Denmark would capitulate at 0800 hours" the next morning. From that moment on, "a strange atmosphere prevailed, everybody appeared happy and relieved but no mood for rejoicing developed," the HLI's war diarist recorded. Morale, he added was "good and rising." This was not, however, the unqualified "100 percent" morale rating he had remarked on that early morning of March 23, 1945, when the battalion had been the first Canadian force to cross the Rhine River as part of the British Twenty-First Army Group's great assault into the heart of Germany. That crossing--codenamed Operation Plunder--had kicked off an Allied advance that had continued virtually without pause until this ceasefire order of May 4. Forty-three days. Nobody at the outset in March had offered bets on how long it would take to bring about Germany's final defeat, although most recognized that the outcome was inevitable and fervently hoped not to be one of the last who must die or be maimed in bringing it about. On the day the historic Rhine crossing had begun, there had only been the promise of much hard fighting ahead. Commanders had sought in the lead-up to the attack to downplay this reality with assurances--as 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade's commander, Brigadier John "Rocky" Rockingham, had declared to the HLI and other battalions under his command--that this was an opportunity to "add further glory to [the brigade's] name." At this stage of the war, however, most soldiers thought glory came at too high a price. The HLI war diarist reflected the general attitude with his matter-of-fact description of a detailed briefing given on March 22, wherein "our phases of the crossing of the Rhine were covered thoroughly." A workmanlike attitude prevailed throughout First Canadian Army, one that looked at each operation, whether large or small, as just another part of a job that would only be concluded when Germany was finally defeated, and those people under its occupation--particularly the millions of Dutch in the still occupied regions of the Netherlands--were at last all liberated. Excerpted from On to Victory: The Canadian Liberation of the Netherlands, March 23-May 5 1945 by Mark Zuehlke All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.