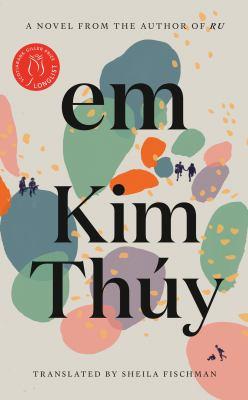

Em

In the midst of war, an ordinary miracle: an abandoned baby tenderly cared for by a young boy living on the streets of Saigon. The boy is Louis, the child of a long-gone American soldier. Louis calls the baby em Hong, em meaning "little sister," or "beloved." Even though her cradle is nothing more than a cardboard box, em Hong's life holds every possibility. Through the linked destinies of a family of characters, the novel takes its inspiration from historical events, including Operation Babylift, which evacuated thousands of biracial orphans from Saigon in April 1975, and the remarkable growth of the nail salon industry, dominated by Vietnamese expatriates all over the world. From the rubber plantations of Indochina to the massacre at My Lai, Kim Thúy sifts through the layers of pain and trauma in stories we thought we knew, revealing transcendent moments of grace, and the invincibility of the human spirit.

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Community Centre | Available |

| Stamford | Available |

Browse Related Items

- ISBN: 9781039000834

- Physical Description 148 pages ; 24 cm

- Publisher [Place of publication not identified] : [publisher not identified], 2021.

Content descriptions

| Language Note: | Translated from the French. |