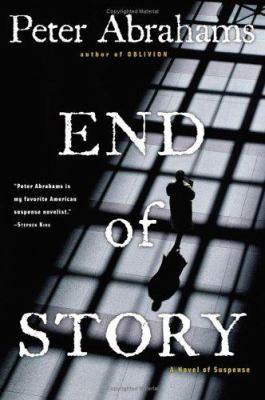

End of story

Aspiring writer Ivy Seidel accepts a job teaching inmates at a prison where she becomes convinced of the innocence of one of her students and embarks on a quest to clear his name.

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Community Centre | Available |

| Victoria | Available |

Browse Related Items

- ISBN: 0060726652

- ISBN: 9780060726652

-

Physical Description

print

321 pages - Edition 1st ed.

- Publisher New York : HarperCollins, [2006]

- Copyright ©2006

Content descriptions

| General Note: | "William Morrow." |

| Immediate Source of Acquisition Note: | LSC 32.95 |

Additional Information

End of Story : A Novel of Suspense

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

End of Story : A Novel of Suspense

End of Story A Novel of Suspense Chapter One "How is going the writing?" said Dragan Karodojic. Closing time at Verlaine's Bar and Grille on Schermerhorn Street, no one left inside except Dragan, the dishwasher, mopping the floor, and Ivy Seidel, the bartender, cashing out. "Not bad," Ivy said. The question--how her writing was going--was the biggest one in her life, with her all the time, and the true answer was she had no idea. What she had was a creative writing MFA from Brown, three summers spent at an upstate fiction workshop, the last on full scholarship, two abandoned novels, sixty-one completed short stories, ranging in length from one page to fifty-eight, and a drawerful of rejection letters. "I myself have idea for novel," Dragan said. "You never mentioned that," Ivy said, taking her tip money from under the cash tray in the register and stuffing it in her pocket. "You are never asking," said Dragan, and the next thing she knew he'd put down the mop and was sitting across the bar. Ivy liked Dragan. Hard not to--six months in the country, big smile full of crooked East European teeth, wide-eyed enthusiasm for things most New Yorkers didn't even notice--but it was after two and she wanted to go home. "What is this thing," Dragan said, "for the cell-phone relays?" He made an expanding gesture with his hands, like a circle growing. "Tower?" said Ivy. "Tower, yes," said Dragan. "Cell tower." And he launched into a long and incomprehensible tale about a cell tower that picks up signals from a shadow world where the souls of all the extinct Neanderthals are plotting revenge. "So," said Dragan, head tilted up at a puppy-dog angle, "I want truth: What is your verdict?" Ivy walked home. A warm September night, as warm as summer, but somehow different. How, exactly? It was important to nail these things down, find the right words. But as Ivy reached her building and climbed the stairs to the front door, the right words still hadn't come. She unlocked her mailbox, number five, found a single letter. The New Yorker . She tore open the envelope. Rejection. A form rejection, of which she'd already collected three from The New Yorker --they used thick paper, might have been sending out swanky invitations, if you were judging just by feel--but this time someone with an illegible signature had added a note at the bottom. Ivy angled it toward the streetlight. The Utah part is really nice. The Utah part? What Utah part? Hadn't she sent them "Live Entertainment," an eight-page story that took place entirely at a truck stop in New Jersey? But then Ivy remembered a brief reference to a snowboarding accident in Alta. How brief? Three lines, if that. Ivy unlocked the front door, walked up to her fifth-floor studio apartment. The staircase, the whole building, in fact, leaned slightly to the right, plus nothing worked properly and repairs never got done, but that didn't keep the rents low. Ivy's room, a converted attic, 485 lopsided square feet, cost $1,100 a month. She went in, slid the dead bolt closed, sat at the table, a café table she'd gotten for free from a failed Smith Street restaurant. Ivy switched on her laptop, found the Utah -passage in "Live Entertainment." He fell but the direction must have been up because he landed in the top of a tree. The only sound was the kid he'd run over, crying up the trail. Far away the Great Salt Lake was somehow shining and brown at the same time. That was really nice? Somehow much nicer than the rest of the story? Ivy read the whole thing over several times without seeing how. She decided to take The New Yorker 's word for it. She was capable of really nice and she interpreted really nice to mean publishable in The New Yorker and all that would come after. Almost three in the morning, but Ivy no longer felt tired. She made herself tea, stood on the table, pulled down the trapdoor with the folding staircase and climbed up on the roof. The only good feature of apartment five, but so good she'd signed the lease even though it was more than she could afford. Ivy stood on her roof, looking west. Over the rooftops, across the river: Manhattan. She had no words for this view. Maybe the movies would always do that kind of thing better. But what the movies didn't capture, at least none of the movies Ivy knew, was the vulnerability. She saw it now, very clearly--the whole skyline could be gone, just like that, as everybody now understood but as no camera could ever show. A tragic magnificence, even futile, like . . . Ozymandias. Wait a minute. Shelley had been this way already. So maybe she was wrong, maybe a really good writer could still-- At that moment, with the lit-up Manhattan skyline before her, -doubly in view, actually, the second image blurred on the water, and a soft September night breeze on her skin, soft and warm, but there was something impermanent about that warmth, even vulnerable, yes, that was it, the answer to the September night and skyline questions turning out to be one and the same--at that moment, Ivy got an idea for a brand-new story. A story about an immigrant, a legal alien in New York, in Sting's words, but this one finds himself turning into a Neanderthal man. Was she stealing from Dragan? No. More like stealing Dragan, if anything. But this was how art worked. There was something brutal about it, a brutality, she suddenly realized, often evident in the faces of the greatest artists, like Picasso, Brando, Hemingway. She remembered the parting words of Professor Smallian at Brown, teacher of the -advanced class and published author of three novels, one of which had been a New York Times notable book: You don't have to be a good person to be a good writer--history shows it's better if you're not--but you have to understand your badness. End of Story A Novel of Suspense . Copyright © by Peter Abrahams. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers, Inc. All rights reserved. Available now wherever books are sold. Excerpted from End of Story: A Novel of Suspense by Peter Abrahams All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.