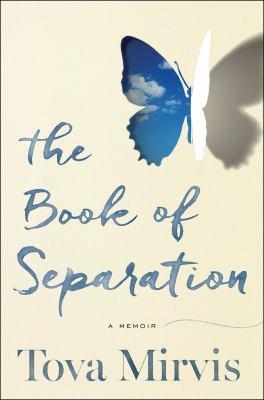

The book of separation : a memoir

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Victoria | Available |

Browse Related Items

| Subject |

| Mirvis, Tova. Authors, American > 20th century > Biography. |

| Genre |

| Biographies. Autobiographies. |

- ISBN: 9780544520523

-

Physical Description

print

302 pages ; 22 cm - Publisher Boston : Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, [2017]

- Copyright ©2017

Additional Information

The Book of Separation : A Memoir

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

The Book of Separation : A Memoir

I stood before a panel of rabbis. I was dressed in the outfit of the Orthodox Jewish woman I was supposed to be: a below-the-knee navy skirt and a cardigan buttoned over a short-sleeved shirt that without the sweater would have been considered immodest. But no matter how covered I was, I felt exposed. What kind of shameful woman, I imagined the rabbis thinking, leaves her marriage; what kind of mother overturns her life? Yet a month shy of my fortieth birthday, after almost seventeen years of marriage and three children, I had upended it all.     On one side of the conference room, the rabbis, in beards, black suits, and dark fedora hats, huddled together to examine the get ââ--ââthe divorce document I was waiting for them to confer upon me. It was black ink hand-scribed on beige parchment, written on behalf of my husband the prior week, when he had come before this same group of assembled men. It didn't matter that I was the one to end our marriage. Jewish law dictated that only a man had the power to issue a divorce.     It also didn't matter how I felt about being in this conference room before this religious tribunal whose job it was to enforce the very rules that I had long felt shackled by. My role was to remain silent as I followed the careful choreography of this ancient ceremony in which no deviations were allowed. A misspelled name, and the document could be nullified. Any tiny irregularity in the ceremony, and the validity of the divorce might one day be called into question.     To ensure that the court had the right woman, one of the rabbis had been deputized to verify my identity. On my cell phone the week before, I'd confirmed that I had no nicknames, no aliases or pseudonyms. My father, I answered, also had none. This kind of scrutiny wasn't new to me. I'd lived my life among the minute rules of Orthodox Judaism. Until now, I'd complied even when I questioned themââ--ââpretending when necessary, doing anything in order to stay inside. I might have fantasized about leaving, but it was never something I thought I'd actually do. If you left, you were in danger of losing everyone you loved. If you left, you were in danger of losing yourself.     When every letter of the document had been deemed correct, the rabbis stood. I tried to keep my face impassive, to pretend that nothing here could touch me.     One of the oldest of the rabbis read the document out loud, in Aramaic, dated the year 5772 from the creation of the world, in the city of Boston, by the Ocean Atlantic.     I, Tova Aliza, was released from the house of my husband.     I, Tova Aliza, was permitted to have authority over myself.     The words might have been ancient, but the freedom they promised seemed radical.     The piece of beige parchment was carefully folded into a small triangle, and I was given further directions: One of the rabbis would drop the parchment into my hands and I was supposed to clasp it to my chest to show I was taking possession. Without saying a word, I was to turn and walk from the room. As soon as the door shut behind me, the divorce would go into effect.     The rabbi who had been appointed as my husband's emissary came over and stood directly in front of me. The other rabbis remained behind the table to witness and thus validate this act. I stood silently before him as instructed, but I knew that I had arrived not just at the end of my marriage but at the edge of the supposed-to-be world. Until now, this had been the only world that existed. Here was the way the world was made, and here was the way the world worked. Here was what I was to do and here was who I was supposed to be. Every decision I'd made up to this point had been stacked on top of these truths. But once the foundation had started to shake, everything else did as well. One by one, the pieces had begun to fall.     The rabbi dangled the folded piece of parchment from his fingers. I cupped my hands and waited.  PART I  New Year, New You  It is September, the first Rosh Hashanah since the divorce, and I've set out on my own.     My three children are with their father, at his parents' house, where I'd spent the past decade of these holidays. My parents, sister, and grandparents are at home, in Memphis, where they will observe this celebration of the Jewish New Year in the Orthodox synagogue I attended every week of my childhood. My friends are in their homes, cooking for family gatherings. My brother, along with four of his eight children, has traveled with throngs of fellow Breslover Chasidim, an ultra-Orthodox sect, to Ukraine, the site of their spiritual pilgrimage. And I am fleeing to Kripalu, a yoga and meditation retreat in Western Massachusetts.     Until this year, I celebrated every Rosh Hashanah the same way I had the one before. To spend this holiday anywhere but in the long solemn hours of synagogue would have been unfathomable. Now, without the rules wrapped tightly around me, I no longer know what to do. Dreading the arrival of this year's High Holy Days, I'd considered pretending they didn't exist and decided to go to Kripalu only because yoga and meditation seemed to be the obligatory way of moving on. ("I assume you're doing yoga," an acquaintance said upon hearing the news of my divorce.) I've told few people where I'm going for the holiday because to do so would be to admit that I'm no longer Orthodox, something that I'm still unsure of myself.     Kripalu is three hours from my house in the Boston suburb of Newton, a highway drive that until recently would have been impossible for me unless I'd studied the maps in search of easy back roads and plotted a route that felt sufficiently safe. For almost a decade of living in the Boston area, I'd been gripped by a fear of driving, steadfastly avoiding rotaries, bridges, and tunnels, driving only when I had to, wishing I could still be in a driver's-ed car equipped with a passenger-side brake and someone who could stop me if I went too fast or too far. I was terrified of getting lost, most of all terrified of the highway. I couldn't bear the sight of those green signs announcing the Mass. Pike or I-95, couldn't merge into the stream of speeding cars. I had nightmares of making a wrong turn onto a wrong street that would lead me to an entry ramp that would take me onto a highway from which I'd never find my way back.     Yet I'm now on the Mass. Pike; the cars are passing me, too many and too fast, and, still shocked that I'm driving on the highway, I clutch the steering wheel, worried about getting into an accident. The biggest fear, though, is not of any injury I might sustain but of the fact that then people will know I'd planned to spend Rosh Hashanah at some suspect retreat center instead of praying in synagogue for a year of blessing, a year of goodness. At the start of all other years, I knew exactly what sort of goodness I was supposed to be praying for, but on this new year, there is no ready prayer, even if I could bring myself to utter one.     It's not just where I'm going for the holiday, but whenââ--ââI'd left too late and now the sun is setting and the clock on my dashboard reminds me how close it is to the deadline of exactly 6:08 p.m. that, until recently, would have divided my day into unalterable domains of allowed and forbidden. It's forbidden to drive on this holiday, and it still feels unfathomable each time I break one of the religious rules prohibiting the use of electricity, against riding in a car. Every transgression feels like a first, each one new and destabilizing.     I speed upââ--ââbetter to break the laws of Massachusetts than the laws of religion that are still binding in my head. If I go faster, maybe I can make it to Kripalu before driving becomes forbidden. But the sun is sinking lower in the sky, and no matter how fast I go, I won't arrive before Rosh Hashanah officially begins. The only option now in accordance with Jewish law would be to pull over by the side of the road, knock on someone's door, and ask to stay for the next forty-eight hours, as though I were a hiker stranded in an unexpected blizzard. If this were a Jewish fairy tale of the sort I'd been raised on, I'd wander in the forest of Central Massachusetts until, in a clearing, with just minutes until the holiday began, I'd come upon a small cabin bathed in golden light and inside, lo and behold, a nice Jewish couple, probably childless, with the holiday candles ready to be lit, an extra place at their table waiting just for me. Excerpted from The Book of Separation by Tova Mirvis All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.