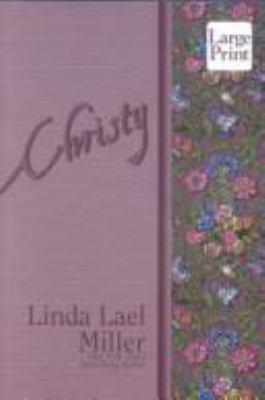

Christy

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Community Centre | Available |

Browse Related Items

- ISBN: 1587241013

- Physical Description 168 pages.

- Edition Large print ed.

- Publisher Rockland, Mass. : Wheeler Pub., [2000]

- Copyright ©2000

Content descriptions

| General Note: | GMD: large print. |

| Immediate Source of Acquisition Note: | LSC 53.11 |

Series

Additional Information

Excerpt

Christy

Chapter 1 "There it is," the marshal said, with obvious relief, doffing his hat to indicate a meandering stream, winking with silvery patches of sunlight as it flowed across the valley tucked amid the peaks of the High Sierras. Trees bristled on all sides, ponderosa pine and Douglas fir mostly, so dense that they appeared more blue than green, though there were splashes of aspen and maple, oak and cottonwood here and there. "That's Primrose Creek. The town's over yonder, about two miles southwest of here." Christy stood in her stirrups and drew in a sharp breath. The air was soft with the promise of a warm summer, and the view was so spectacular that it made her heart catch and brought the sting of tears to her eyes. Megan, riding beside her, drew in a breath and then exclaimed, "It's Beulah Land!" She pointed eagerly. "And look -- that must be Bridget and Skye's house, there by the bend in the stream. Oh, Christy, isn't it grand?" Some of Christy's own delight in their arrival faded. She and Megan had passed the war years in Great Britain, at the insistence of their mother, Jenny Davis McQuarry, who had kicked up considerable dust back in Virginia by leaving her drunken rounder of a husband, Eli, and running off with a titled Englishman. Jenny's new love, a relatively minor baron as it turned out, and not an earl as he had led her to believe, was nonetheless the master of Fieldcrest, a small estate in the heart of Devon. He had promptly sent both his bride's daughters off to St. Martha's, a boarding school outside London -- over Jenny's anemic protests -- and had never made a secret of the fact that he would have preferred to leave them behind with their ruffian relatives in the first place. When Jenny had died suddenly of a fever in the winter of 1866, he'd been quick to pack them off to America. Christy would have been overjoyed to return, except that by then they had almost no family left; their father and Uncle J.R. had both been killed in the War between the States, and their passage had been booked when word of their beloved grandfather's death reached them in the form of a terse letter from Gideon McQuarry's lawyers. Already grief-stricken at her mother's passing, and now Gideon's, Christy had been in a private panic. She'd succeeded in putting on a brave front, for Megan's sake, and had impetuously written her cousin Bridget, an act she would soon regret, offering to sell their half of the inheritance, hers and Megan's, as outlined in the copy of Gideon McQuarry's will. There had not been enough time for a response from Bridget before their ship sailed, and, besides, she did not have the right to dispose of Megan's share of the bequest in the same way as her own. With only their clothes -- including ugly school uniforms and a few ball gowns garnered from their mother's wardrobe -- a set of china that had belonged to their grandmother Rebecca, and the few modest jewels Jenny had managed to acquire during her two tempestuous marriages, they crossed the sea and arrived in Virginia to find strangers living in the house they had loved. Granddaddy was buried in the family plot, alongside the beautiful wife who had died in a riding accident when the girls were small. Uncle J.R. rested beside his father, his grave marked with an impressive granite stone declaring him a Union hero. Christy and Megan's father, Eli, lay next to Rebecca, but a little apart from the others, or so it seemed to Christy. He had fought bravely, his wooden marker claimed, under the direct command of General Robert E. Lee. There had been no reason to stay in Virginia, with everything and everyone they loved gone. "Ma'am?" the marshal prompted, bringing Christy back from her musings with a snap. He was about thirty years of age, she estimated, though she'd been doing her best, ever since they'd left Fort Grant that morning not to think of him at all. He was easy in his skin, with a habit of whistling cheerfully, and just being near him made Christy feel breathless and off-balance, as though the ground had been jerked from beneath her feet. She had expected these emotions to pass while they were traveling together, especially since they had disagreed practically every time they had occasion to speak, but they had only intensified, and she blamed him entirely. "I reckon we ought to ride on down there and let them know you're here." Behind Christy and the marshal, Caney waited at the reins of a wagon she'd driven all the way from Virginia. Also known as Miz Blue, Caney had been at the farm when Christy and Megan arrived from England; she and her man, Titus, had worked for Granddaddy as free people, since he'd never kept slaves. Recently widowed and "frightful lonesome," Caney had chosen to accompany them on the trip west to the spanking new state of Nevada -- the state whose wealth of silver had helped to finance the Union cause. "Yez, Missy," she said now. "This here wagon seat be harder than the devil's heart. I want to sit me down someplace comfortable!" Christy turned her head and gave her friend a narrow look. The daughter of a Baptist preacher, Caney had learned to read and write before she was six, and her grammar was as good as anybody's. Still, she liked to carry on like an ignorant bond servant once in a while, for reasons she had never troubled herself to share. Caney met Christy's gaze straight on, and without flinching. Her mannish jaw was set, and her dark eyes glittered with challenge. "I will surely be glad to look upon Miss Bridget and Miss Skye again," she said. "They's my own precious babies, just like you and Miss Megan. Oh, I will be glad, indeed." Megan was flushed and beaming at the prospect of a family reunion, and Marshal Zachary Shaw was obviously chafing to get on with whatever it was he did to keep the peace in the town of Primrose Creek. It seemed that Christy was quite alone in her reluctance to come face-to-face with their Yankee cousins. She hoped neither Caney nor Megan remembered the last time she and Bridget had been together; they'd gotten into a hissing, scratching, screeching fight, right there in the front yard at the farm, and would surely have killed each other if Uncle J.R. and a laughing Trace hadn't hauled them apart and held them till they were too exhausted from kicking and struggling to go at it again. "I declare a place as grand as that must have a bathtub," Megan mused, squinting a little in the bright spring sunshine. Then, as if that decided the matter, she spurred the little pinto pony she was riding, on loan from the army as was the spirited sorrel gelding Christy had been assigned, down the trail toward the rambling log house, with its glistening glass windows and smoking chimneys. Caney headed that way, too, which left Christy alone on the ridge with Mr. Shaw. She shifted uncomfortably in the saddle, while he swept off his disreputable leather hat to run one forearm across his forehead. In spite of herself, and all her efforts to ignore him, she was aware of the man in every sense. He was in his shirtsleeves, having shed his heavy coat earlier and bound it behind his saddle with strands of rawhide, and his suspenders were exposed. His shoulders and chest were broad, tapering to a lean waist, and his hair, the color of new straw, wanted cutting. His eyes seemed to see past all the barriers Christy had erected over the years, and that alone would have been reason enough to avoid him, but there was much more to the allure than that. Indeed, it had an almost mystical quality, not merely physical but a thing of the soul and the spirit as well. "You'll be all right now," he said, and Christy couldn't tell whether he was making a statement or asking a question. In the end, she didn't care, or so she told herself. She just wanted to see the back of Zachary Shaw, once and for all. Bad enough she'd had to put up with him for three days and two nights on the trail. "Yes," she replied, as stiffly as if she'd been addressing a scullery maid in the kitchen at Fieldcrest. "Thank you very much, Marshal. You may go now." His eyes lighted with amazed amusement, and his mouth tilted upward in a cocky grin. "Well, now. That's mighty generous of you, Lady McQuarry," he teased. "Your giving me permission to leave your presence and all." He'd made no secret of the fact that he thought she was high-handed and uppity, but Christy felt a flood of startled color surge into her face all the same. No matter what she said, he'd probably manage to misconstrue her words, make her seem condescending, even snobbish. Well, she wasn't going to let him have the satisfaction of upsetting her any more than he already had. "Good day," she said, tartly this time. He chuckled, shook his head again, reined his spectacular cocoa-colored stallion around, and rode off toward the southwest without slowing down or looking back. For some thoroughly unaccountable reason, she was disappointed. Quite against her will, let alone her better judgment, Christy watched him until he disappeared into a grove of cottonwood trees, their leaves shimmering in the breeze like silver coins stitched to a gypsy's skirt, and she had an awful feeling that he knew it. Well, tit for tat, she thought. She'd certainly caught him watching her often enough during the trip from Fort Grant, his face a study in perplexed annoyance. At last, she decided she'd been stalling in order to avoid the inevitable meeting with Bridget and rode slowly down the steep grade, following Megan, who was traveling at a lope now that she'd reached flatter ground, and Caney, rattling along in their ancient mule-drawn wagon, a relic of better days at the farm. There was no sense in putting it off any longer. When proper greetings had been exchanged, she'd ride over and have a look at her and Megan's side of the creek, decide where they might put up a cabin of some sort to shelter them until they could afford a real house. Bridget was standing in the doorway now, her abundant hair, as pale as Christy's was dark, swept up at her nape in a loose chignon. She was wearing a blue calico dress that matched her eyes -- Christy's were charcoal gray -- and she was sumptuously pregnant. She laughed as Megan jumped down from the pinto's back, hurrying toward her like a filly gamboling through a field, and took the girl in her arms. Then, weeping and exclaiming for joy, she turned to embrace Caney. The merriment had already gone on for some time when Skye came rushing across the clearing, basket in hand, overjoyed to see Megan, her old playmate, and Caney, whom neither she nor Bridget had probably expected to see again, ever. Bridget's boy, Noah, stood staunchly at his mother's side. His resemblance to his late father, Bridget's first husband, Mitch, jarred Christy a little. He was four or five, and there was a spark of formidable intelligence in his eyes. She managed to dismount, but her legs seemed to be sending roots deep into the ground, and she couldn't make herself take a single step forward. When she did contrive to move, it was only to turn and flee. She promptly came face-to-chest with Trace Qualtrough. She'd known that he and Bridget were married -- the marshal had told her in one of their brief, stilted conversations -- but that didn't lessen the impact of actually seeing him again. The memory of their last meeting was as much a thorn in her side as that of the scene she and Bridget had made, brawling in the dirt like a pair of tavern wenches. She'd declared her eternal love and begged Trace to wait until she was older; she would come home from England then, and they would be wed. He'd smiled sadly, kissed her forehead, and said he didn't plan to take a wife, ever, and she'd felt as though he'd plunged a knife into her. Older now, and handsomer than before, if that were possible, he nonetheless had no effect whatsoever on her emotions. She supposed she'd become jaded, reflecting on her father's wild and irresponsible ways and the unfriendly nature of her mother's second husband. "Running away?" he teased, taking a gentle hold of her shoulders. Trace assessed her with brotherly dispatch and pulled a face. "That isn't like you, Christy. Besides, I believe you might be able take Bridget this time, her being pregnant and all. You'd want to watch out, though. She bites." Christy laughed, almost giddy with relief that her little-girl adoration for this man was gone. Perhaps the old animosity between herself and Bridget would prove as fleeting, and they could become friends. Or at least establish a truce of some kind. "Have you forgotten that we were practically children at the time?" "Not for a moment," he replied, and took her elbow lightly in one hand. "Come on. Let's get this done. Bridget's dreading it as much as you are." To her credit, Bridget met them halfway, wiping her hands unconsciously on her apron as she approached. Her expression was solemn, even wary, but not unfriendly. "Come inside," she said in a quiet voice. "You must be longing for a cup of hot tea." Christy had been braced for censure; their legendary catfight notwithstanding, she and Bridget had never been close, as Skye and Megan were. Long before their fathers had taken separate sides on the questions of states' rights and secession, they'd bickered over dolls, ponies, lemon tea cakes, and, in time, matters of decorum. Bridget had been a veritable hoyden, a blight upon the McQuarry name, while Christy had endeavored to behave as a lady -- most of the time. The only thing they'd had in common, besides the proud, stubborn blood of Gideon and Rebecca McQuarry simmering in their veins, was a deep interest in horses. Both had been expert riders almost from the moment they could sit a horse, and at that point, where they might have found an affinity, they'd become rivals instead. "Thank you," Christy murmured with a nod. She hadn't enjoyed real tea since she'd left England, for such luxuries were still rare in Virginia and impossibly dear when they could be found. It made her grind her teeth just to think of how poor she and Megan really were, but if she had her way, they'd never have to fear poverty again. Bridget linked her arm through Christy's and tugged her toward the open doorway. "Tell me," she began, "about the farm. Are the new people diligent? The barn wanted painting when we left -- " The inside of the house was cool and spacious and smelled pleasantly of baking bread. There was a good stove at one end of the large central room, and three doorways led into other parts of the house. A gigantic rock fireplace stood opposite the kitchen area, faced with handmade rocking chairs and a cushioned bench, and just looking around spawned a bittersweet mixture of sorrow and pleasure in Christy. Pleasure because the place reminded her so much of the farmhouse back home in Virginia, and sorrow because it wasn't her house at all, but Bridget's. Always, Bridget. "Christy?" Bridget spoke gently. Cautiously. She glanced back and smiled to see that she and Bridget were alone. Convenient, she thought. No doubt, the others considered themselves peacemakers, even diplomats, giving the two cousins a chance to work out their long-standing differences by staying clear for a while. "They've put on a new roof," she said, referring to the new residents at the family farm, as though the thread of the conversation had not been dropped. "And I do believe they mean to shore up the stables before there's any painting done." Bridget ducked her head, sniffled slightly. Of course, she still missed the homeplace, as did Christy. It was a part of them both, that faraway land of gentle hills and blue-green rivers, and it probably always would be. The deed had borne a McQuarry name since the Revolution, though now it belonged to Northerners, fast-talking carpetbaggers who'd strolled in and claimed the place for back taxes. "Do sit down and rest yourself," Bridget said, without looking at Christy. She hurried to the stove, while Christy took a seat in one of the rocking chairs and stared into the dying fire. "When is your baby due?" she asked presently. It had taken her that long to come up with a safe topic. Bridget raised a happy clatter with the teapot, and there was a note of eager anticipation in her voice when she replied. "June," she said. "I'm hoping for a girl, though Trace thinks we ought to have several more sons first, so that our daughters will have older brothers to look after them." Christy ached with envy, not because Bridget was well married, not even because she was expecting her second child. She was sure to find a husband of her own in a place where women were regarded as a rare treasure, and she would almost certainly have babies, too, in good time. But it was evident that Bridget and Trace had married for love, for passion; she could not expect the same good fortune. No, for Megan's sake, and for her own, Christy was determined to marry for much more practical reasons. She sat up a little straighter in the rocking chair. "This is a fine home, Bridget," she said. "You've done well." "Trace deserves most of the credit for the house," Bridget replied lightly, stretching to take a china teapot down from a shelf. "He built it with his own hands. The barn, too." Christy tilted her head back and looked up at the sturdy log rafters. Perhaps one day, she reflected, this ranch would be to Bridget and Trace's children and grandchildren what the farm had been to several generations of McQuarrys. What legacy might she, Christy, leave to her own descendants? "Sugar?" Bridget said. "Milk?" It was a moment before Christy, weary of the road, realized her cousin was asking what she took in her tea. "Just milk," Christy replied. "Please." She studied Bridget as she sat down in the next rocker. Bridget's spoon rattled as she stirred sugar into her tea. She bit her lower lip once, started to speak, and stopped herself. "You received my letter?" Christy guessed. "Asking you to buy Megan's and my share of the land?" She paused, savored another sip of tea, stalling. "It was a mistake to make such an offer. I was distraught. I'm -- I'm sorry." Bridget nodded. "I understand," she said. "Still, I'm prepared to pay a fair price. If you're ever of a mind to sell." Christy set her teacup atop the small table between the two chairs. It nettled her that Bridget not only had Trace, Noah, and the unborn baby but this grand house as well. Even as she spoke, she knew she was being unfair, but she couldn't help herself. Things were so complicated when it came to anything concerning Bridget. "You're not content with the twelve hundred and fifty acres you have here?" Bridget sat up a little straighter, and a blue tempest ignited in her eyes. "It is not a matter of contentment," she said. "Furthermore, Trace and I own only half of the property, as Skye inherited an equal share. I merely assumed that since you'd written -- " "I told you -- I've changed my mind," Christy said as she pushed back her chair a little more forcibly than was required and got to her feet. Bridget closed her eyes for a moment, in a bid for patience. "Christy, please. Sit down. Hear me out." Christy began to pace the length of the huge hearth, her arms wrapped tightly around her middle. "You might as well know it right now. I mean to use that land -- my share, anyhow -- as a dowry of sorts." Bridget's mouth dropped open. She looked purely confounded. "A dowry?" "Yes," Christy replied. "Even rich men expect them, you know. In fact, they seem to prefer property over gold or currency, in these uncertain times." She stopped, met Bridget's bewildered gaze. "I mean to marry a wealthy man, for Megan's sake and my own." She threw the words at her cousin's feet like a gauntlet. "The richest one available. Who would that be, Bridget?" Her cousin's jaw line clamped down hard while she made a visible effort to contain her legendary temper. "If you want to keep the land, that's your right. But only a fool marries for money. I've held many an opinion where you're concerned, Christy McQuarry, but I never thought you were a fool." Christy felt color rise to her face. "I'm not you, Bridget. Lucky stars don't tangle themselves in my hair or fall at my feet -- I have to fight for the things I want." Bridget's own expression softened from anger to sadness. "Christy," she said softly. "It must have been hard, coming home from England -- " "Damn England," Christy spat. "We were miserable there -- shunted off and forgotten. Made to feel like poor relations, even beggars." "Christy," Bridget repeated. "Oh, Christy." "Don't," Christy said before her cousin could go on. She didn't want Bridget's concern, damn it. Didn't want her pity. She had swallowed enough of her pride already. "You've always been fortune's favorite. You were Granddaddy's favorite, too. And Mitch's. And -- Trace's." "Granddaddy loved you," Bridget insisted. "He was heartbroken to lose you and Megan. He never forgave Jenny for taking you away, or Uncle Eli for letting you go." Christy did not reply; she would have choked on the painful lump that had risen in her throat. She had never doubted her grandfather's love, as she had her mother's and certainly that of Eli McQuarry, her wild and reckless father. Nor did it particularly trouble her that she would have to make her own way in a world that would grant her no special concessions whatsoever. She had the grit, the strength, the intelligence, and, yes, the beauty to get what she wanted?and she would not be turned from her course. "Christy," Bridget said once more when she started for the door.But Christy kept walking and did not look back. The town of Primrose Creek was hardly more than a cow path with a wide spot, to Zachary's way of thinking, but it had its own sturdy log jailhouse and four saloons. He supposed that said something about a place, that it boasted a hoosegow and more than one watering hole, but no schoolhouse and no real church, either. The Methodists and Baptists held services in borrowed tents, but a hard rain or a high wind could send them scrambling for the shelter of the Silver Spike, the Golden Garter, the Rip-Snorter, or Diamond Lil's. Truth to tell, this state of affairs hadn't troubled him much; he wasn't a religious man, despite his good Christian raising, nor was he especially fond of liquor, and had heretofore concerned himself with neither churches nor beer halls. He was even-natured, for the most part, a man with simple wants and wishes. He had a way with horses and little else, and he made a point of minding his own business. Moreover, something had gone cold within him the day Jessie died in his arms, so while he enjoyed a sporting woman as well as the next man, he never thought about settling down. Now something had changed, and there was no denying it, much as he would have liked to do just that. Some inner foundation had shifted, sent cracks streaking through the walls he'd erected to last a lifetime. Feeling a chill -- spring weather in the Sierras was a fickle thing -- he shoved a piece of wood into the stove near his desk and prodded it into flames with the poker. A day ago, he'd showed up at Fort Grant, looking to do his duty as marshal, fetch a gaggle of women safely up the trail, and be done with it. He'd gone, however grudgingly, but the man who'd ridden back up the track wasn't the same as the one who'd ridden down it. And what had wreaked all this havoc? One look at Miss Christy McQuarry, that was what. He'd seen pretty girls before, of course, even out there in the back of beyond, but Christy -- Miss McQuarry -- was more than pretty. She was beautiful. That first sight of her, with her gleaming dark hair and charcoal-gray eyes, her perfect skin and slim, womanly figure, had struck him with the force of a log shooting off one end of a flume, and he was still reeling. God in heaven, he even liked fighting with her. He rubbed his beard-stubbled chin and squinted into the cracked shaving mirror next to the window. He didn't look all that different, but he was thinking some crazy thoughts, that was for sure. He wanted to dance, for God's sake, and not with one of the ladies who plied their trade over at the Golden Garter, either. He wanted an excuse to put his arms around Christy McQuarry, that was a fact, and the music was optional. Furthermore, he'd started to imagine what it would be like, living in a real house with curtains at the windows, raising a passel of kids, just as his own mother and father had done. He made twenty dollars a month, he reminded himself, and that was when the town council had the funds to pay him, which was only intermittently. He felt his forehead with the back of one hand and grinned ruefully at his own image in the looking glass. No fever. At least, not in his head. Christy faced the ramshackle structure with as much courage as she could muster. According to Trace, the place had originally been a Paiute lodge. It had a leaky hide roof, stitched more with daylight than rawhide, and he and Bridget had kept horses there in inclement weather. They'd lived in the place, too, while their house was being built, but Christy took small comfort in that knowledge. "You must be outta yo' head," Caney said, hands on her hips. "Miss Bridget and Mister Trace have that nice house over yonder, and you want to live here?" Christy turned to face the woman she considered her only true friend, exasperating as she was. "Go ahead and stay with them, if that's what you want," she replied, keeping her voice crisp. "Well, I ought to, that's fo' sure. They got real beds over there. They got windows and a roof that don't show no sky through it -- " Determined, Christy began sweeping out the rock-lined fire pit in the center of the building, using a broom she'd improvised herself from twigs and slender branches, and she was brisk about it. "Fine. You're getting old, and you need your comforts. Besides, you got spoiled living at Fort Grant all winter." Caney rose to the bait like a trout leaping for a fly, and Christy, having her back to the woman now, smiled to herself. "What you mean, I'm gettin' old and spoilt? I ain't but forty-two, and I can do the work of any two mule-skinners. Got you and Miss Megan across all them plains and mountains, didn't I?" "You did," Christy said, and pressed her lips together. "You think I ain't got the gumption to sleep in a place like this? Laid my head down in many a worse one, I have." Christy smiled, swept, and said nothing. "Drat it all," Caney groused. "You know dern well Miss Megan will stay here if you do, out of plain loyalty, and that leaves me with no choice at all, because I wouldn't sleep a wink for thinkin' of the wolves and the outlaws and the Injuns gettin' to you, after all I done went through to bring you here -- " Shame jabbed at Christy's conscience; she'd promised herself that she wouldn't be like her mother, wouldn't use other people to get her own way, wouldn't use another's weakness to her advantage, and here she was, doing precisely those things. "I'm sorry," she said, turning and meeting Caney's level gaze. "I shouldn't have said anything. I was trying to influence you -- " Caney gave a guffaw of laughter. "Were you, now?" she said, her bright jet eyes twinkling. "Well, two can play at that, young lady." Christy pretended to swat at her friend with the makeshift broom. "You were pulling my leg the whole time." "'Course I was," Caney said, grinning now. "If you're set on stayin' here, then I will, too." She looked up at the deer hides sagging overhead. "We gonna live in this place, Miss Christy, we gotta put us some boards up there, and some tar paper, too, if we can get it. You have any of that money left? What you got for your mama's watch and pearls back in Richmond?" Christy sank onto a bale of hay and sighed. "It took every penny to buy the mules and food and sign on with the wagon train. I'll take the cameo into town tomorrow. Surely some miner will want it for a present." Tears stung behind her eyes at the prospect of yet another stranger taking possession of one of Jenny's belongings, but she would not shed them. She had certainly had her differences with her mother, but she'd loved her. In spite of everything, the losses, the separations, the grim, unhappy days at St. Martha's, and the even unhappier visits to Fieldcrest, she'd loved her. Caney's large, slender hand came to rest on Christy's shoulder. "Life'd be some easier for you if it weren't for that McQuarry pride of yours," she said quietly. "Now, let's gather some firewood and carry in the trunks from that wagon out there. We push some of these bales together, we can make us some beds. Better'n sleepin' under the wagon like we did whilst we was travelin'." Christy laid her hand over Caney's, squeezed. "What's wrong with me, Caney?" she whispered. "Why can't I be beholden to Bridget or anybody else, even for something as basic as a real roof over my head?" "I done told you already," Caney said. "It's that ole devil, pride. You got it from your granddaddy -- he sure had him plenty, ole Mister Gideon McQuarry. Turns a body cussed, that's fo' sure. But it makes you strong, too. Keeps you goin' right on when other folks would lay down and whimper." Christy blinked a few times, stood up, and went back to her sweeping. When that was done, she and Caney brought in the trunks and pushed bales together to make three beds. There were plenty of quilts, hand-stitched by Rebecca McQuarry herself, and knitted woolen blankets, for Caney had rescued them from the laundry before she'd left the farm. They spread them over the prickly surfaces of the hay and made jokes about princesses and peas. By the time Megan returned, accompanied by Skye, twilight was falling, and there was a cheerful blaze crackling in the middle of the lodge. The mules had been let out to pasture, along with horses borrowed from the army, their things had been brought in from the wagon, and Caney had a pot of beans, dried ones left over from the journey west, simmering on the fire. Megan gleamed as though she'd been polished, and her bright red-gold hair caught the firelight. She and Skye were both barefoot, having waded across the stream, and carried their shoes by the laces. "I had a real bath," Megan said, as proudly as if she'd never taken one before. "I used hot water and store-bought soap, too, and I didn't even have to hurry in case it got cold, because Bridget kept filling up the tea kettle and warming it on the stove." Christy, seated on yet another bale of hay, smiled and leaned forward to stir the beans with a wooden spoon. "Well, now. I'm sure you must be entirely too fine to keep company with the likes of Caney and me. I expect you'd rather spend the night with Skye." Megan was clearly torn between a perfectly natural yearning for creature comforts -- she had done without them for a long time, without a single complaint -- and a strong devotion to her older sister, and it moved Christy deeply, seeing that. Forced her to look down at the fire for a moment and swallow hard. "Bridget sent you a dried apple pie," Skye put in quickly, as if fearing the silence, and set a covered basket on the dirt floor, close to Christy's right foot. "She can't bake a decent cake to save her life, but she's got a way with pie dough." Christy spoke carefully. Quietly. "Please tell her I said thank you," she told the girl gently, then shifted her gaze to Megan. "You go on across the creek with Skye, now. The two of you have been apart for a long time -- you must have a lot of giggling to catch up on." Megan looked doubtful, and at the same time full of hope. "You're sure?" Her voice was small. "You wouldn't mind?" "I won't be alone, Megan," Christy pointed out tenderly. "I've got Caney to keep me company." Megan hesitated just a moment longer, then bent and kissed Christy on the cheek. "I'll be back first thing in the morning," the girl promised earnestly. "You'll be needing a lot of help. Maybe I can catch us some fish for supper." Christy reached out, patted her sister's hand. As children, Megan and Skye had been thicker than the proverbial thieves. She wasn't about to let her own problems with Bridget come between them. "That would be a fine thing," she said. With that, the girls vanished into the night again, and their happy chatter trailed behind them like music. "You did the right thing, lettin' that girl go like that. I know you worry about her whenever she's out of your sight," Caney observed, taking the spoon from Christy's hands and serving up a plate of beans for each of them. "She'll be safe with Trace and Bridget," Christy said. Safer, certainly, than in an old Indian lodge with no door and no windows and only the flimsiest excuse for a roof. The two women ate in companionable silence, both of them sick to death of boiled beans, and Caney insisted on carrying the dishes down to the creek for washing. When she returned, Christy had put on a nightgown, unpinned her waist-length hair, and begun to brush it with long, rhythmic strokes. She'd lit a kerosene lamp against the descending darkness and set the basket containing Bridget's pie inside one of the recently emptied trunks, in hopes of discouraging mice. It would be a fine treat for breakfast. Caney undressed in the shadows and donned her own night dress, a fancy red taffeta affair trimmed in lace. It had been given to her by a sick woman she and Christy had tended while they were crossing the plains with the wagon train. The lady, one Lottie Benson, accompanied by a man she said was her brother, must certainly have had a story to tell, but Christy hadn't dared to ask her. Besides, it was kind of fun, just speculating. "I reckon you know that good-lookin' marshal has an eye for you?" Caney asked, stretching out on her spiky bed with a long-suffering sigh. The idea warmed Christy in a way no nightgown, taffeta or flannel, could have done. She blew out the lamp and lay down to take her night's rest. "Nonsense," she said. "You're imagining things." Caney sighed again, a comfortable, settling-in sigh. "We'll see 'bout that," she replied. "We'll just see." Copyright © 2000 by Linda Lael Miller Excerpted from Christy by Linda Lael Miller All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.