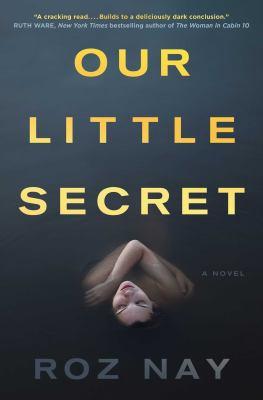

Our little secret : a novel

The detective wants to know what happened to Saskia, as if I could just skip to the ending and all would be well. But stories begin at the beginning and some secrets have to be earned. Angela is being held in a police interrogation room. Her ex's wife has gone missing and Detective Novak is sure Angela knows something, despite her claim that she's not involved. At Novak's prodding, Angela tells a story going back ten years, explaining how she met and fell in love with her high school friend HP. But as her past unfolds, she reveals a disconcerting love triangle and a dark, tangled web of betrayals. Is Angela a scorned ex-lover with criminal intent? Or a pawn in someone else's revenge scheme? Who is she protecting? And why?

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Community Centre | Available |

| Victoria | Available |

Browse Related Items

- ISBN: 9781501142802

-

Physical Description

print

229 pages ; 23 cm - Publisher [Place of publication not identified] : [publisher not identified], 2017.

Additional Information

Our Little Secret

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

Our Little Secret

Our Little Secret chapter 2 My mother always taught me not to ask questions you don't want answers to. Mind your manners, Angela. You're so nosy, so grabby. You're so needy; have I taught you nothing about being a lady? Twenty years I lived with my parents and we never really talked about anything. We were just moles fumbling along in the same dark tunnel. These days when all three of us meet, we blink at each other in the bright surprise of my adulthood and flounder for a point of reference. But if I think about it now, maybe my mother was right. In among all her competitive disapproval lay a gristly knuckle of truth: don't ask what you don't want to know. Detective Novak, I don't trust your curiosity. I prod my forefinger on the chrome of the table, leaving a smeared fingerprint. "I'll tell you all I can, on two conditions." He waits. "I know Saskia. I know what she's like. Is it really true she's been missing since last night?" He nods. "I want to know why you think it's a homicide case. She might have just wandered off. Maybe she flew back to wherever she came from." He pauses, frowning. "At this point we're considering all possibilities." "Good, because you shouldn't rule anything out. You don't know what people are capable of." That one he writes down. I wait for him to finish, the full stop at the end of his line carefully pressed. He lifts his head. "What's your other condition?" "My what?" "You said there were two conditions." "Oh, I don't want to talk about Saskia the whole time." Novak's teeth are flat at the front, four of them in a row. "She's kind of the main event." A black thread dangles from the hem of my shirt. I coil it around and around my forefinger until the skin at the tip shrieks purple. "I'm sorry to break it to you, Detective, but the story I have for you isn't really about her. There's a skill to finding where a tale truly begins, and trust me, there was action long before there was Saskia." I yank the thread free, roll it into a tiny ball and launch it to the floor. "Start wherever you like, Angela. I'm a captive audience." We study each other. "Am I a suspect, Detective Novak?" He uncrosses and crosses his long legs. "Like I say, the investigation's ongoing. At this stage we're just filling in the blanks. We don't know for sure what we're looking at. And you're helping us form a . . ." He cups his hands as if around clay. ". . . a clearer picture." "I doubt I can help. I know HP more than I do Saskia, and most of what I can tell you is a decade old." His mouth smiles but his eyes don't. "Just tell me what you know." I shrug. "Okay, here we go." So, Detective Novak, can we talk about me for a change? In my experience, it's not a subject that gets much forum and I have a lot to say. It might even end up being cathartic. Thank you--I'll take it from that slight incline of your head that you'll let me off-load for a while, whether or not you have a choice. Let's go way back and begin with how my parents moved a lot. My mom and dad bonded over their restlessness and rushed to get married in it. They met as amateur actors in a play and once they had me, we were up and moving every three years as if our life was a stage production they thought they were touring. One of my earliest memories is of being four, maybe, and in the middle of cutting out a picture of a turkey from the grocery-store coupons. My fat little hands were squashed right into the scissor handles, cutting in a curve, when my mom started jangling her keys next to my head and telling me we had to go, right now, baby, out the door, let's go. Right now, leave that, just leave it. She yanked the scissors out of my hand and stood over me while I struggled to find my shoes. I went through my whole childhood like that. Ready to be yanked away. The moves were career-related for my father--he's always been a man with one eye on the success ladder, although if you ask me he must have been climbing the rungs in his slipperiest socks. Ad astra per aspera, Angela--to the stars the hard way. It was tiring watching him. Still, my mother was happy to accompany him as long as each step felt like a social climb. There was a giddiness to their choices in those early years, a strange excitement. Darling, just imagine! Each time they left a place, my parents must have believed they were on their way to somewhere they might actually be happy. Moving when you're fifteen is terrifying. It's not fun, it's not an adventure, it's not a wild ride to wonderful things, baby. In Grade 9 I said good-bye to my friends and watched them fade away from me even while I was still standing there. When people get older, they're supposed to cope better with separation, but I don't know whether that's true. Are we honestly meant to believe the important ones will stay with us wherever we go? We drove three hours northwest to Cove, Vermont, in the fall just as Grade 10 began. You probably love this town to death and all, Detective Novak, you're probably New England born and bred; but I've got to tell you, the first time we drove down Main and Oak Streets it looked like we'd arrived in the sister town of somewhere more exciting, the kind of place you move to because the housing's cheaper. Sure, Vermont is all covered bridges and maple-candy shops, and life is like the lid of a Christmas cake tin, but when we drove into Cove town center, there was a hardware store, a scattering of bars with faded HAPPY HOUR banners over their doorways and a Tastee Delite with a hand-scrawled sign in the front window that read GET YOU'RE POPSICLES NEXT JULY, YOUR AMAZING--I swore I'd never eat there. The town's curling rink looked like a Cold War bomb shelter from the outside, and the riveted metal of the roof clanged with raindrops as we drove by with the car windows down. The house we bought was sad and gray and looked hunched like it was coughing. There was a shoe in the driveway. In the middle of the front lawn was an iron stake driven deep into the dirt, with a rusted chain on the grass. "Dog owners." My mother shuddered to my father. "David, we'll need a commercial cleaner." Do you like living in a town of only four thousand people, Detective Novak? Isn't it a cozy little community? Dad knew and liked the principal of the high school and felt the move to a smaller place would somehow benefit my chances of getting into a good college. It's all about class sizes, my dear. Teacher-student ratio. Let's shoot for the Ivy Leagues. He took a job at the Cove Municipal Library, giving up his research post at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston because he had become obsessed with my education. Either he'd lost the trail of his own success and was now starting to sniff out mine, or else he was trying to relive his glorious Yale days where he aced his Classical Civilization class and spent heady afternoons reading The Iliad under the shade of the maples. I never wanted to leave the city. Small towns are a soap opera: you're either acting or you're watching. I went to Lakeside High, although I'm sure you already know that. It was a flat-roofed brick building with basketball hoops out front that had long ago lost their netting. The first day in that school my palms smelled tinny and sour from gripping the iron handrails that led up to the front entrance. The locker they gave me still had stickers in it from the kid before--rainbows that were plastic and puffy and crinkled when you pressed them. I pried them all off with my thumbnail. At every school I attended, gym teachers sighed when they saw me coming, and Lakeside High was no different. At the end of gym on that first Monday, I went to change back into my regular clothes and there were knots in the ends of my pants, pulled so tight that two people must have put their full weight into the job. I couldn't tease the knots apart. By the time I sat down in defeat, the locker room had emptied. "Angela, is it?" The teacher came in with her class list clasped to her rock-hard chest. "Angela Petitjean?" She said it like this--pettitt-gene. Not much of a linguist. "What's happening here?" She wore a polo shirt with all the buttons done up, and her bangs were hair-sprayed to one side. "Who did this? Holy smokers, they put some effort into it." As she spoke, she grunted and ground her fingers into the knots, easing them loose. "Okay--here. Now, pick up the pace! You'll be late to your next class." My pants had a crimped hemline for the rest of the day, like an '80s disco look. I knew who did it; I knew right away because two girls followed me down the hallway laughing when I emerged from the gym. And they were everywhere: waiting outside the washroom, behind me in the lineup for lunch and three lockers down, leaning against the wall while I tried to get my books organized for English class. The taller one wore dark-purple nail polish and a T-shirt that showed her belly button. Pierced. The other girl dressed identically, even down to the love-heart laces in her sneakers. What is it about teenage girls that makes them impossible to tell apart? I thought it was all in the styling, the makeup, the cloning of boy-band music and favorite movies. Now I realize what bonds and homogenizes them: panic. Haven't you noticed, Detective Novak? Girls of fourteen move together in a band of cruelty, always searching for somebody to terrorize as long as it keeps the spotlight off them. They'll hunt in twos or more because if you're standing alongside the sniper, it's unlikely you'll be the one in the scope. "You're new, aren't you?" the tall one said. "Yeah, we're not really okay with that." They giggled. "We like to be asked before things change." I didn't say anything back, but I remember reaching as far into my locker as I could, short of climbing in there and shutting the door. "What's with your pants?" Just then a voice stopped them. "Back up there, sisters." I peeped around the edge of my locker and saw a tall boy a few doors down. He was about fifteen, olive-skinned, blond, with a sleeveless Metallica T-shirt that showed the early bump of deltoids. He wore sandblasted beads around his neck and a navy baseball cap with a D on the front. "Oh, hey, HP." Girl number one shook back her bangs. "Oh, hey," Girl number two echoed. "Where'd you come from?" She stretched gum from her mouth and twirled the glistening loop with a forefinger. "Swim practice." He slammed his locker door and walked towards me. I think my head tried to turtle down into my shell in that moment as I stood there in my crinkly pants, wide-eyed, holding my English textbook. "Come on," he said. "I'll walk you to class." This is where the story begins. Grade 10, eleven years ago. Mark it on your sheet, Detective Novak. I'm telling this like it's the beginning of a love story; I'm catering to your needs as a listener. But we both know that's not where the narrative's heading, right? I mean, it's bound to get much darker--why else would I be telling it in a police interview room? I like that you're humoring me and letting me steer the ship for a minute. Of course, you might feel I'm not cutting to the chase quickly enough, the way you're tapping your toe on the linoleum like that; but to be fair, if the chase is a murder, then why am I even here? You want me to just keep going? Okay, whatever you say. HP and I started down deserted hallways, him scuffing an empty raisin packet along the floor every fifth step. I hadn't walked beside many boys before--it was all I could do to sneak a glance at the side of his smooth face. A small curve of hair kicked up from under his hat. "Don't let Christie Burbank work you over. She's got nothin'. Just call her Spermbank, that'll slow her down." He stopped to tie the lace of his high-top. "And the other one's Danielle Moyzen. I call her Moistbum." His face craned up towards me. "What's your name, anyway?" "I'm scared to tell you," I said, and he laughed. When he stood up, he pulled the top of my English book down from where I held it clenched against me. "Angela Petitjean," he said, properly, reading the label on the front. "English Ten. Okay, you're in here." He opened the classroom door for me. As I walked through it, he added, "See you around, Little John." It was the only class of the day I went into smiling. He walked me home, too. It turned out he lived a block up from me in a house with a huge birch tree out front. I was ahead of him, trudging along in my gray Converses, when I heard footsteps catching up with me. I turned and there was HP, running with his thumbs hooked under the straps of his skull-embossed backpack. "Hey," he said. "Hey." We walked in silence as I racked my brain for a conversation to have with him. He knew I was doing it, too, because after a minute he looked down at me. "Nothing?" "What does HP stand for?" I blurted. It came out really loud. We'd already reached my driveway so I stopped walking and mumbled, "This is me." "Old Man Sneider's place? You guys bought this house of horrors? Wow, when we were little, we used to hide behind this wall right here and watch for ghosts in the windows." "Who did?" "Me. Kids around here. This house was the only one that never got decorated on Halloween. It never needed to." HP sighed nostalgically. "And there used to be a shit-scary dog that lived here. I walked to school with a rock in my hand all of Grade Nine." He took his baseball cap off and ruffled the hair at the back of his neck. He had a line around his head from where he'd thrown his hat on after swimming. "You got a dog?" "We had one back in Boston but it got re-gifted." "By who?" He said it like he was about to get a posse together. "Mom gave him to a family across town. I think it was a hair thing." HP nodded like he understood the logic. We stared at each other. He stretched. "I'll walk by here tomorrow morning at eight. If you're here, you're here." I pressed my back against the brick gatepost and looked up at him. "What's HP stand for?" "My last name's Parker, but that's all you're getting." He put his baseball cap back on. "Some secrets you have to earn. I'll see you around, Little John." He stalked off, his fifteen-year-old legs gangly in his skinny jeans. I watched him kick a pebble down the sidewalk, catching up, then punting it on. He did it all the way home. From then on, the only days I didn't walk to school with HP were those when one of us was home sick. And as it turned out, the greatest alliance anybody in the school could have was with HP. I never had any trouble from anyone ever again, including Burbank and Moyzen. As we got older--Grade 11--girls waited for him at the gates and he'd peel off, flapping me a wave as he joined hands with the latest one. He had a constant stream of female fans; I'd often be in the washroom while a huddle of Grade 11s consoled the latest HP casualty as she dabbed her eyes. Shhh, they'd whisper, their eyebrows panicked. That's her, that's Little John. Wait till she leaves. Girls threw themselves at HP's feet, and he hadn't figured out who the good ones were yet. I doubt he even cared. By seventeen he was captain of the swim team. He had bright blue eyes and arms like Poseidon. Even Mr. Cameron, the school principal, thought he was cool and high-fived him in the lunchroom. HP called Mr. Cameron "Jerry" or, on some days, "Jer." When it came to the girls, though, I wished HP would be pickier, and maybe slow down a little on the hand-holding. Like my mom always told me, it's graceless not to discriminate. I never understood why HP had chosen me as his friend, or how I'd gotten an all-access pass to him. It was like having a key to the White House. He told me everything he thought and felt and wanted, and I don't think he told anyone else in the world--not even Ezra, his best buddy. Ezra was a goofball and a jock, and if you told him you even had a feeling about anything he'd probably give you a charley horse and call you a pansy. Sometimes HP painted pictures on thick, fibrous paper and wrote me letters over the top of them, letters about the good things in life--how your skin feels after a day in the ocean; the smell of asphalt before it rains; the way old people's hands wrap around coffee cups in restaurants. Ezra would have punched HP in the face if he'd found out about those. I kept all of the letters--I still have them. In the summer after Grade 11, HP and I sat with our backs against the trunk of the old birch tree in his front yard. We met there a lot, often after dinner when I'd walk the block barefoot and call for him at his open front door. His parents rarely shut the door and never locked it. "If anything's coming for us," HP's dad used to say, "it'll come just as good through a window." It was a warm night--August, I think--and the cicadas were screeching. Mrs. Parker came out with pie, but I didn't want any. "It's peach." HP took a plateful and a fork, hefting off a huge chunk. "Are you sure, Angela?" HP's mom was small like a sparrow, with papery-soft skin. She spoke in short sentences and whenever she could, touched HP on the shoulder or head in passing. "I'm fine, thanks, Mrs. Parker. I just ate." "Don't get cold out here." She drifted back to the house. "You two. I don't know." HP rolled his eyes. "She thinks we're soul mates. She said so at dinner. Says she's never seen two kids more comfortable." A couple of huge bites and the pie was gone. "I told her to stop being emotional." "I like that." I picked up a leaf and ran its supple edge across my bare knee. "I believe in soul mates, but my mom says there's no such thing. She says there are tons of people a person could be with, not just one. Believing in a soul mate is like believing in Santa. According to her it's only ever about timing--who you meet and whether you're ready. That's all it is." "Downer." "Yeah." I moved my foot so it lined his. "That's what I said." HP shuffled his back against the bark of the tree like a bear scratching. "Actually, you know what? I'm with your mom. There are tons of people a person can be with." He raised his eyebrows and brushed pie crumbs from his shirt. "You're certainly testing the theory." "So far not so many soul mates, though. More wing nuts than soul mates, if I'm keeping a tally." I flung my leaf at his foot. "That's because you only date people on the outside." "What does that mean?" "You don't know who any of them are!" He banged my knee with his knuckles. "How am I supposed to know they're wingers when I ask them out? It's like friending someone on Facebook and then realizing they're nuts when you look at their page. You've entered into a contract by then." "Delete! Easy." "Okay, well, we can be soul mates. I'll date the wingers and you can be my soul mate." "Another healthy plan." With my weight against his side I could feel the teenage-boy leanness of him through the fabric of his sweatshirt. I could have straightened back up but didn't. "One more year of school." He sighed. I loved how his brain did that: the leaps were almost visible. "I can't wait to be done." "Are you going to travel?" We'd talked before about the adventures that were out there--the shark dives in South Africa, the climbing of the Matterhorn. But now our final year was before us, and with the freedom to pick a direction, the world seemed less conquerable. Going places was scarier than talking about them. "I don't know. My dad's on me about getting a trade. He's offered me an apprenticeship with him as a carpenter." HP shrugged. "Sounds okay." "God, what is it about parents who have only one child? My folks are on me constantly about which school this and what scholarship that. Jeez, it's like they had a kid just so they could obsess and over-steer and maybe get a second shot at the glory. You know what I'm talking about." I felt HP wince and pull at the neck of his hoodie. "My folks aren't like that. They're just looking out for me. And the truth is I'm not an only child." He paused. "I had a brother." The volume of the cicadas suddenly increased, or else it was the white noise in my head. I pushed myself up so I could look at him. "You what?" "He died when I was four." I thought of his quiet mother and his dad's apathy about locking the door. They already knew they couldn't keep the world out. "Oh, HP, why didn't you tell me before? That's terrible." "I don't talk about it a lot." He rubbed his eye. "And I don't want you to, either." "No, of course--" "I was only four. My brother choked at the dinner table right there." He nodded towards the kitchen window, which was open and amber with light. "I was sitting next to him. He was a year younger than me." I must have made a sound then because he faltered and put his arm around me. I could feel his ribs against mine. "I don't remember a whole lot, just the fear of it. The panic. My dad wasn't home, just my mom." "Christ." HP breathed in and out once, lifting me and settling me back against the birch. "You know, life's not controllable. You do the best you can with the chances you get. And on you go." "How didn't it kill your parents?" "It did. It devastated them. But they went on. So did I, I guess." He knew himself so well. He was miles ahead of me. "Why didn't you guys move?" "Because pain isn't in houses." He swallowed hard. "And when something like that happens, it ties you to the house. It's like a scar you grow into. I can't explain it." He picked up a twig and rolled the peeling bark with his thumb. "So I'll probably take the apprenticeship with my dad, and the high school's making noise about me coaching their swim team. That sounds all right, too. I don't know about the travel thing." "Jesus," I said, still reeling. "If I was you, I'd want a change of scene. Let's go somewhere else. We can go together." "For what? To 'find ourselves'? Like I said, Little John, I'll be me wherever I go." We sat silently for a few minutes, watching the light from inside HP's house. I could hear his mother clanking pots in the kitchen. "I don't need to go anywhere, either," I said at last. "Here's fine for now." He drew me into a hug and pulled his hood up, so I could see only strands of beachy hair poking out and the strong line of his chin. In the spring of Grade 12--so, eight years ago--my class planned a late-June camping trip out at Elbow Lake for grad. Mom was weird about me going, which was dumb, given how she'd dragged me all over the country growing up. Apparently her new thing was for me to stay home more. "And will there be adult supervision?" She twisted the pearl earring in the lobe of her ear. She'd been chopping carrots and had flecks of peel stuck to the sinews of her forearm. Behind us on the counter her food-preparation Les Misérables blared: she'd turned it up just before I came in, and we had to shout over it to be heard. "And have you finished your paper on Faust? You need to maintain your grade point average, darling. Beat everyone else and finish strong." "What?" I said, my head in the fridge. There was never anything good to eat: it was all baba ghanoush and tapenade. I pulled out a strawberry yogurt drink that HP must have left there. "Honey, don't say what, say pardon me. And drinking yogurt is manly. Get a spoon." My mother's hair draped forwards over her shoulder as she worked, and she batted it away with a heavily bangled wrist. "It's runny, Mom. The yogurt is runny!" I walked over and turned the CD volume down, then stood against the kitchen drawers, slurping from the container. My mother grimaced. "So can I go on the camping trip or what? Or pardon me?" "Don't be clever, Angela. Nobody likes a show-off." Dad wandered into the kitchen humming a Tchaikovsky bass line. It was rare to see him. When he wasn't working at the library, he spent every hour in his study at home poring over ancient Greece. He knew everything about Orpheus and nothing about me. When he reached for a slice of carrot, Mom slapped his hand. "Who else is going?" She grasped the knife and chopped. This was the key answer to get right. "HP." I waited. Even the mention of his name swept light onto her face. Did women of all ages adore him? I rolled my eyes but she didn't catch me. Mom had decided long ago that I'd marry HP. I could ask her a question about anything else four times and she wouldn't hear me. Say HP's name, though, and her head snapped around like a barn owl's. I'd been buddies with him for close to a year before I first introduced him to my mom. I wasn't much of a talker back then, and if my parents ever asked how school was going, I gave them only monosyllables. But one day Mom intercepted HP and me on our walk home. "Oh, hi!" she said, not looking at me. "Who's your friend?" HP readjusted the strap of his backpack and stood up straighter. "I'm Shelley Petitjean"--Mom wheeled past me--"what a pleasure it is. Angela failed to mention she had such a handsome chaperone for the school commute." "This is HP, Mom. He lives a block up." "I bet he does." HP gave my mom a kind of hybrid handshake-high five across the gate. "Pleased to meet you, Mrs. Petitjean." "Oh, call me Shelley, for goodness' sake." Her finger pointed at his chest, making him glance down as if he'd spilled food there. "You're the quarterback on the football team." She tapped her lip. "No, wait, you're a junior hockey player. Beach volleyball?" She shook her head. "You've got me all turned around." "He swims," I mumbled. "See you tomorrow, HP." "HP? What does that stand for?" He shifted his baseball cap. "It's a secret," I said. "Is it? Will you tell me later?" Mom whispered to me. "So." HP cleared his throat. "Nice to meet you, Mrs. Petitjean. I'll see you around, LJ." Mom looked at me quizzically, then looked back at HP. "Is there a prom soon? You should ask Angela to it." "Mom!" I started to walk into the house. "It's, like, in a whole year's time and besides, gross." Mom followed me in, waving good-bye as HP took off. "Angela, you need to plan ahead for your milestone moments." She hurried after me, stepping over my bag as I dropped it in the hall. "I'm telling you--Angela, stop moving and listen to me--prom's a major life event and that boy is your prom date. Milestone moments!" Now at the kitchen counter, Mom paused in her carrot chopping. "Oh, darling, you didn't tell me HP was going camping. That's great. Now I know you'll be safe. He'll look after you." "Well, hold on a minute, Shelley." Dad adjusted the waistband of his track pants over his dress shirt. He took his reading glasses off and held them up to the light, huffing hot breath onto each pane. "Is it an overnight thing?" "Yes, Dad. It's a camping trip, with tents and sleeping." "And we're sure that HP will keep a good eye on you, are we?" "Of course we are, David. He adores her. Doesn't he, Angela?" I shrugged. "He adores her. You should see the way he looks at her." Mom sighed and put her hand to her bony chest, the edge of the knife blade glinting near her chin. "Although frankly, honey, you could make more of an effort. Is that a boy's sweater? And why do you insist on wearing your lovely dark bangs so they hang over your superior bone structure? If I were to take a photo of you right now and show it to you in ten years, you'd be horrified." "You can only go if you've done all your homework," Dad said. "I'll have graduated by then!" "And if you have everything in place with college plans. Did I tell you I heard back from Reggie McIntosh? He's head of Classics at Oxford." He abandoned his search for crackers and rubbed his hands together while I yawned. "You might be in with a chance for this fall if you keep your head down. Reggie's working it so you take your freshman year over there--he owes me a favor, so he's all but sneaking you in the back door." I drained the last of my yogurt. "Oxford University, England--get excited, it doesn't get any more Ivy League than that! You have such potential, my dear . . ." He trailed off. If he was waiting for thanks he didn't get it. I couldn't care less about Ivy League schools. The only reason I went along with his push for academia was because it got me out of their crosshairs. "We can talk about it properly another time . . . Angela? Look at me. Here's what I have to say about this camping trip: If all your work is done . . ." He raised a pale index finger. ". . . and you keep your wits about you, it should be acceptable. But be careful: I know how teenage boys think. I was one of them, too, you know." "No, you weren't, David." Mom put her knife down and wiped her hands on her hips. She turned to me. "You can go, darling." I turned Les Misérables back up. It had been easier than I'd thought. So if all the other girls, including my mom, were crazy about HP, how did I feel about him? I know that's what you're thinking, Novak. Was I in love with him? My mother would say I was, but she also drove us to prom with the theme tune from Titanic playing on her car stereo, so don't believe anything she says. Why was it so crucial that I define my feelings for him? If you ask me if he dominated my teenage years, that's an easier one to answer. The truth is I don't know if I was ever like the other girls. I knew HP too well. He was handsome; I liked seeing him with his shirt off; but when I caught myself looking at him, it felt kind of . . . obscene. We were friends. We were at ease and had no need to decipher ourselves. Not, at least, until after the camping trip. Excerpted from Our Little Secret by Roz Nay All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.