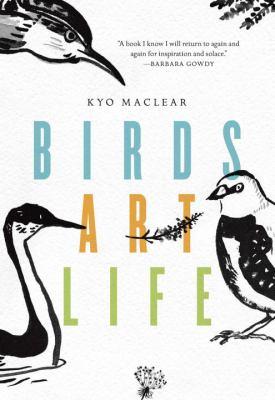

Birds art life

For fans of When Breath Becomes Air and H is for Hawk, an elegant and exuberant memoir about a year of bird-watching, reflection and art--a field guide to things small and significant. For Vladimir Nabokov, it was butterflies. For John Cage, it was mushrooms. For Sylvia Plath, it was bees. Each of these artists took time away from their work to become observers of natural phenomena. In 2012, Kyo Maclear met a local Toronto musician with an equally captivating side passion--he had recently lost his heart to birds. Curious about what prompted this young urban artist to suddenly embrace nature, Kyo decides to follow him for a year and find out. Intimate and philosophical, moving with ease between the granular and the grand view, this memoir is an unconventional field guide that celebrates the particular madness of loving and chasing after birds in a big city. It celebrates the creative and liberating effects of keeping your eyes and ears wide open, and explores what happens when you apply the core lessons of birding to other aspects of life. In one sense, this is a book about disconnection--how our passions can buckle under the demands and emotions of daily life--and about reconnection: how our distractions can also sustain us. On a deeper level, it takes up the questions of how we are shaped and nurtured by our parallel passions, and how we might come to love (and protect) not only the world's pristine natural places but also the blemished urban spaces where most of us live. Birds Art Life follows two artists on a year-long adventure."--

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Community Centre | Available |

Other Formats

Browse Related Items

| Subject |

| Maclear, Kyo, 1970- Bird watching > Ontario > Toronto. Birds > Ontario > Toronto. Nature > Psychological aspects. |

- ISBN: 9780385687515

-

Physical Description

print

259 pages : illustrations ; 20 cm - Publisher [Place of publication not identified] : [publisher not identified], 2017.