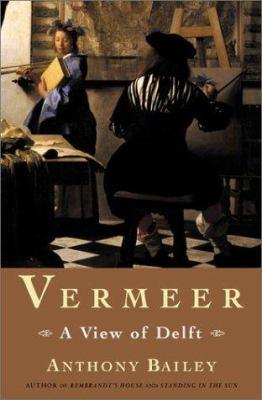

Vermeer : a view of Delft

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Victoria | Available |

Browse Related Items

| Subject |

| Vermeer, Johannes, 1632-1675. Painters > Netherlands > Biography. Delft (Netherlands) > In art. |

| Genre |

| Biographies. |

- ISBN: 0805067183

- Physical Description xiii, 272 pages : illustrations (some color), map ; 22 cm

- Edition 1st ed.

- Publisher New York : Henry Holt and Co., 2001.

Content descriptions

| General Note: | "Simultaneously published in the United Kingdom under the title 'A view of Delft : Vermeer then and now' by Chatto & Windus, London"--T.p. verso. "A John Macrae Book." |

| Bibliography, etc. Note: | Includes bibliographical references (pages 257-262) and index. |

| Immediate Source of Acquisition Note: | LSC 41.95 |

Additional Information

Vermeer : A View of Delft

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

Vermeer : A View of Delft

Chapter One The World Turned Upside-Down Monday morning, 12 October 1654. Within the close-packed town of Delft -- a long box of streets and canals surrounded by a defensive wall and a watery girdle of canal and river that served as a moat -- laundry was spread to dry in several thousand back-yards. The skyline of orangey-red pan-tiled roofs was dominated by three towers: that of the Town Hall, rebuilt forty years before; that of the Nieuwe Kerk -- Nieuwe to distinguish it from the Oude Kerk, though by now it was a hundred and fifty years old -- which stood at the opposite end of the large Market Place from the Town Hall; and that of the Oude Kerk, which backed on a canal called the Oude Delft, across which prosperous three- and four-storey houses faced each other. The massive tower of the Oude Kerk looked as if it might any day fall on the neighbouring houses; it was at least 2 metres out of plumb but nearby residents -- long used to its dangerous tilt -- weren't holding their breath. At street level the usual sounds of the day could be heard. Carriages and hand-barrows rattled over the brick- and cobble-paved streets. Mallets, wedges, and saws were being used in timber-yards and coopers' workshops. Hammers clashed against anvils in smithies. The click and clack of looms rose from several hundred houses where, as was common, people worked in their own homes, making serge and worsted, silk and satin. Some trades of course were quieter; for example, those where tapestries were being woven, and canvas and clothing sewn. And some were just about silent. In fifty or sixty private houses and in a dozen or so ateliers attached to potteries, artists wielded brushes as they painted canvases and panels, plates and tiles.    So it was in a small house in the Doelenstraat, a narrow street in the north-east of the city, close to the archery butts and headquarters of the city militia and to the former convent of the Poor Clares, the Clarissen, now used as a store for army munitions. In this Doelenstraat cottage an artist named Carel Fabritius sat in front of his easel. Fabritius was thirty-two years old. He was preoccupied with a portrait, the subject of which -- Simon Decker, the retired verger of the Oude Kerk, who lived not far away on the south side of the Jan Voersteeg -- was sitting to one side behind the easel.    Fabritius was a highly talented artist, a good-looking man with a broad nose and full lips, the son of a schoolteacher and a midwife from Midden Beemster, a village in a reclaimed lake area just north of Amsterdam. He had ten siblings including two brothers who also took to painting. Their father was an amateur painter; their grandfather a Calvinist preacher who had come north from Ghent in Flanders in 1584.    In the not very long course of his life so far Fabritius had lost his first wife and his two children. He had been a carpenter and builder -- hence the surname Fabritius, from the Latin faber , `maker'. In Amsterdam he had worked in Rembrandt's studio for a year or more, and had picked up from the older man -- the greatest artist in that great city -- many skills in the handling of paint and in ways of considering subject-matter. He had painted among other things a biblical scene, The Raising of Lazarus , and a portrait of an Amsterdam silk merchant, Abraham de Potter. Delft was the home town of his second wife, Agatha, who was a widow when he met her. They lived first in her family's house on the Oude Delft canal, before moving to the Doelenstraat. By 1654 he had been in Delft for four years, and for the past two years a member of the Delft Guild of St Luke, the association which regulated the profession of painters, as well as those of faiencemakers, bookbinders, glassmakers and so on. Thus Fabritius was now qualified not only to work in Delft but to sign his pictures, market them, and accept apprentices.    His reputation had been growing in his adopted city. Although a number of his pictures -- some unfinished, all unsold -- were stacked against the walls of his studio, others were out in the world, some with local dealers such as Reynier Vermeer, some with private patrons. One such patron was Dr Theodore Vallensis, a prominent Delft burgher and dean of the Surgeons' Guild, who had commissioned Fabritius to paint murals in his house on the Oude Delft. Fabritius's former fellow-Rembrandt pupil, the Dordrecht painter Samuel van Hoogstraten, wrote in 1678 that these `miracles of perspective' could be compared with the frescoes of Giulio Romano in the Palazzo del Tè of Duke Vincenzo Gonzaga in Mantua, with a magical character that made the space around them look larger than it was. Fabritius had also done murals for a Delft brewer named Nicolaes Dichter, who owned a brewery called De Vekeerde Werelt , `The World Turned Upside-Down'; this name was taken from an old Netherlandish saying which artists were accustomed to illustrate with an inverted orb hung outside an inn and maybe a drunken figure or two -- the world, it was suggested, could be a personal one that went topsy-turvy. Fabritius had also worked with the artist brothers Daniel and Nicolaes Vosmaer on a big sea picture. He seems to have tried out all sorts of approaches and many kinds of subject, in various sizes.    A very small creation of his was a View in Delft painted in 1652 -- a miniature but slightly dizzymaking prospect. A man sits at an outside stall displaying two stringed instruments and contemplates the cobbled roadway where the Oude Langendijk meets the Vrouwenrecht. The road climbs steeply over a humped bridge. There's a single tree in leaf, houses, and the Nieuwe Kerk, strangely small, seen from the rear. The distorting effect is like that of an amusement arcade mirror, with different elements of the picture in irregular focus, an unnaturally wide angle of view, and disconcerting discrepancies of scale. The sunlit viola da gamba and lute loom large in the foreground, almost overwhelming the black-coated and black-hatted man sitting in the shadows, with the thumb of one hand propping up his chin. The instruments may be symbols of love (as in music `the food of love'). The hanging sign may be advertising an inn; it shows a swan -- perhaps a symbol denoting a happy death (as in swan song), perhaps a hostelry of dubious reputation (as with the swans that drew the chariot of Venus). The experts also disagree as to whether the man is trying to sell the instruments or is waiting for a young woman. Most agree that the tiny size of the picture (15.4 x 31.6 cm, 6 1/16 x 12 7/16 in.) enhances its success; it is a tour de force ; the view both is and isn't Delft as Fabritius's friends and colleagues would have recognised it.    Hoogstraten said that it was a pity that Fabritius never worked on a royal building or church, where -- he implied -- his ability to create such startling illusions would have been seen to greater advantage. But in fact the View in Delft is happy in its size; only its context is unclear. Was it intended for a peepshow or perspective box, of the kind that Hoogstraten himself made?    Other Fabritius works included two assumed-to-be self-portraits, in which Rembrandt's influence is visible, the person being painted looking out at the viewer with a direct, perhaps slightly disgruntled, gaze: in one, with his black chest-hair blatantly exposed, he is set against a wall of peeling plaster; in the other, he wears a military breast-plate and stands against an intimidatingly stormy sky. There was also a painting called The Sentry . In this, a soldier in distressed breeches sits dozing outside a weirdly dysfunctional archway -- is he on supposed guard-duty at the Clarissen convent munitions store? -- while being watched by a much more alert dog.    A seemingly more straightforward work was The Goldfinch (see colour section), painted earlier in this same year on a little panel of thick wood that may have been once built into a cabinet. The bird -- known for its skill at drawing water from small containers -- is called a putterje in Dutch and there may have been a pun intended here on the name of Fabritius's patron Abraham de Potter; goldfinches were also known for liking thorns and thistles and could therefore in that symbol-conscious age be a useful symbol of Christ's Passion. But none of these aspects seems particularly important. The painting is Fabritius's masterpiece. And it is also just a depiction of a goldfinch. The little bird, chained to a curved rail on top of its box, seen against a rough white plaster wall, looks life-size. Broad brush-strokes become visible when the viewer gets close, but at a short distance The Goldfinch -- head turned inquisitively towards us -- is miraculously real. The little bird might have been a household pet, though we can only assume, from the loving familiarity with which it is painted, that it belonged here in a small house in the Doelenstraat.    Despite portrait commissions, times weren't easy for Fabritius and Agatha. Recently, for the Delft town council, he had done two coats of arms, one large, one small, for a payment of twelve guilders; this was equal to his registration fee with the Guild of St Luke, half of which he still owed. He was in debt to a waiter at the nearby Doel inn, with 110 guilders owed for food and drink. The death of the Prince of Orange, William II, in November 1650, had apparently cut off commissions expected from that influential quarter. But debt was part of an artist's life. Fabritius's neighbour, Egbert van der Poel, who was also thirty-two, had not long ago agreed to pay off, partly with pictures, a loan of 217 guilders made to him by Arent van Straten, landlord of another inn, the Golden Fleece. A relatively new member of the St Luke's Guild, Reynier Vermeer's twenty-two-year-old son Johannes, had only been able to afford a down payment of one and a half guilders on the six guilders' entry fee he owed as a local man who had trained outside Delft. Some of their colleagues were saying that as far as Delft was concerned, it would be all downhill from now on; it was time to move elsewhere. Egbert van der Poel had been talking of moving to Rotterdam. Adam Pick had sold up and gone to Leiden, while Emanuel de Witte and Paulus Potter had decided to try their hands in Amsterdam. Shortly before ten-thirty on that same Monday morning, a little more than a hundred yards away, a man named Cornelis Soetens approached the old convent buildings in which the States-General, the Dutch national assembly, maintained an arsenal -- one of six in Delft. Although there was now peace with Spain, both England and France -- by sea and by land respectively -- were still a real threat. The fact that the former Clarissen convent was jammed full with munitions and explosives was something the residents of the neighbourhood were aware of, though they kept it at the back of their minds. It hadn't deterred the builders of several streets of new houses between the Lakengracht and Verwersdijk, in an area known as the Raam, where the old frames for stretching cloth in the open air used to stand.    Soetens, a clerk for the States-General, had the task this morning of removing a 2-pound sample of gunpowder from the store -- a sort of tower, three-quarters buried in the convent garden, that was known as t'Secret van Holland . It held about 90,000 pounds of gunpowder, mostly underground. Soetens was accompanied by a colleague from The Hague, wearing a red cloak, and by a servant. A lantern was lit, a door to the store was opened, and Soetens's companion handed his fine cloak to the servant so that it wouldn't get dirty on their errand and told him to take it home. The two men went in and down the dark stairs to collect their sample.    Some minutes passed. It was still an ordinary Monday morning in Delft. And then it seemed as if the heart of creation had opened up. The air filled with an immense noise that multiplied and magnified into an all-encompassing roar. Five huge successive explosions merged with one another. The earth shuddered and shuddered again. Flames rose and an intense heat fanned out in a searing wave. Walls fell and bits of houses soared upwards along with their contents: beams and floorboards, bricks and roof-tiles, glass and pottery, pans and tools, clothes and children's toys flew up and outwards; so did curtains, carpets, doors, windows, knives and spoons, loaves of bread, barrels of beer. And so, too, did once-living things, some now barely alive, many dead. Trees; plants; men; women; children; cats; dogs; pet birds. They were whole or in pieces: arms, legs, torsos, heads, rose and fell. The vibrating air was thick with smoke and dust and rubble, and strangely wet as well, for the water in the canals had been blown high.    Some thought it was the end of the world. Others believed that heaven had split asunder, that they had seen the mouth of hell gape wide. And then those who still had their hearing began to make out the cries of people from under fallen houses.    The Thunderclap radiated out from the Secret of Holland in the former convent garden. It travelled across the flat country's meadows, lanes and waterways to other towns. Doors slammed in Haarlem and Delfshaven.    Here in Delft, the shock wave passing through the ground caused houses in the first few hundred yards to fall down. The shock wave sweeping through the air made other buildings collapse and hurled pieces of them outwards into nearby structures. The rush of heat meant that trees and buildings caught fire. In the tightly packed streets around the Clarissen convent the effect was catastrophe; just about every house was flattened between the Geerweg to the north and the Doelenstraat to the south, between the city wall to the east and the Verwersdijk to the west. The guild-halls of the civic guards and the surgeons were among the buildings destroyed. Beyond this zone of total disaster, tiles were stripped and roof-timbers sent crashing down, but though the roofs and walls of the two great churches were slightly damaged and their window-glass was cracked and smashed, the churches themselves still stood above the skyline of the city. Many trees had been chopped off cleanly at ground level while those whose trunks still stood had blackened boughs bereft of leaves. Where the Secret of Holland had stood was a deep hole which soon filled with black water.    It was a little while before those outside the immediate area of calamity pulled themselves together. The rush of many to help was affected by caution -- perhaps there were more explosions to come. For some, fright predominated, and they fled the city in panic. There were also many impediments in the way of those who wanted to assist: canal bridges down, streets blocked, bodies and parts of bodies everywhere, fires burning. But soon many residents of the less damaged parts of the city were there, levering beams, pulling aside clumps of brick and plaster, scrabbling and digging with their hands. Some looked for family members and friends. Some heard cries and screams and sobs, and worked to rescue strangers. Many of those killed were cloth-workers. In the house of one man who made serge, all were dead: the master, his wife, their servant-woman, their children. The neighbourhood girls' school was in ruins and twenty-eight children and their teachers fatally injured. One woman who had a clothing business had been hit on the head by a door lintel and killed, and dead too were four of her seamstress apprentices; three were more fortunate, two being pulled alive from under a wall and one from under a loom, where she had fallen. In the Doelenstraat Egbert van der Poel's daughter was one of those found dead. So, too, in Carel Fabritius's house were his mother-in-law Judith van Pruijsen, his assistant-cum-pupil, Mathias Spoors, and the verger Simon Decker. The painter himself was extricated from the wreckage badly crushed. But he was still breathing and was carried off to the hospital near the Koornmarket.    It was a wet evening. The wind went round to the south-west and strengthened; rain fell steadily. The torches of those looking for victims were frequently blown out. To assist the overstretched Delft physicians, doctors arrived from outside the city -- from Schiedam, Rotterdam, and The Hague -- to bandage wounds and amputate limbs. People were still being pulled alive from ruined buildings through the next day or so. Twin babies were found unharmed in their cradles in a wrecked house in which their mother lay dead. One seventy-five-year-old man was found alive, lying on his bed, in a house that had collapsed over him. A little girl just over a year old was pulled from the rubble still in her high-chair, clutching an apple in one hand, with only a scratch to show her rescuers, at whom she laughed. The record for survival apparently belonged to an elderly woman who was brought forth from the wreckage of a large house four days after the explosion, still conscious; she asked those who were lifting her, `Has the world come to an end?' Unfortunately for many it had. There were some who had survived the Thunderclap itself but been trapped, such as two women on whom a wall fell at half-past six that evening of the 12th as rescuers tried to dig them free. Many of the victims were unidentified, but among those who were eventually named was the painter of The Goldfinch . Carel Fabritius had died of his wounds less than an hour after he had arrived at the hospital. No trace was found of Cornelis Soetens and his colleague from The Hague. * * * A veil is drawn over what occurred after Soetens and his companion went down into the well-named Secret of Holland that morning. Did one of them drop the lantern? Was a spark struck -- say, by a metal padlock or key hitting a paving stone or a brick? Whatever the impulse, a devastating force had been suddenly released in the Second Quarter of Delft. The power that had slammed doors in Haarlem and Delfshaven broke windows in The Hague and shook them in Amersfoort and Gouda. The great thump was heard in Den Helder, the port on the tip of North Holland, and even, so it was claimed, a little further off, on the North Sea island of Texel, 60 miles away. And here was a disaster which had touched almost everyone in Delft; it was hard to find a family who hadn't lost a member or hadn't had one injured. The explosion's effects had been felt by young and old, the well-to-do, the hard-working, and the poor. It had come out of the blue, without any warning whatsoever. In a war, those who enlisted knew what to expect; in a war, civilians recognised the possibility of looting and murder. This had been a total surprise. There hadn't been time even to pray.    People came from all over to gaze and wonder and of course to express sympathy. The States-General sent a letter of condolence. Among the distinguished visitors who toured the shattered city was Elizabeth Stuart, sister of the executed King of England Charles I; in 1613 at the age of seventeen she had married Frederick, the Elector Palatine, who was briefly King of Bohemia. She had lived in The Hague for the last thirty years, with the help of pensions granted by the States-General and the English Parliament, and in recent times had been surrounded by many exiled Stuart supporters to whom she was fondly known as the Queen of Hearts. She wrote to her son Charles Louis, the current Elector Palatine, on 19 October, to see if she could get his help in redeeming a diamond necklace which she had been forced to pawn, and added: I am sure you hear of the blowing up of the magazine of Delft this day seven-night. I went upon Thursday to see it, you cannot imagine how the town is ruined, all the streets near the tower where it was are quite down, not one stone upon another. The host of the doole [possibly the Doel tavern] there was standing upon the threshold of his door, when the blow was. It stunned him a little, and after he turned himself to go into his house and found none, [he saw that] it was quite turned over.    To Sir Edward Nicholas, one of the aides of her nephew (who was to become Charles II), she wrote: `It is a sad sight, whole streets quite razed ... it is not yet known how many persons are lost, there is scarce any house in the town but the tiles are off.'    There were funerals to attend, though the Reformed Church made no great ceremony of obsequies at any time and the services were simple. Carel Fabritius was among the fifteen who were buried in the Oude Kerk two days later, as were his mother-in-law and Simon Decker. The irony may have been noticed by some that Decker's job would have included the duty of keeping the register of burials; Fabritius's father had fulfilled the same task in Midden Beemster. As the Queen of Bohemia had suggested, the death toll remained uncertain, though one report gave the number of identified dead as fifty-four (which happened to match the last figures of the year); thirteen years later the city historian Dirck van Bleyswijck put the figure between five hundred and a thousand -- a wide enough margin for error. Some bodies had been dismembered or decapitated. Roughly a thousand were seriously injured, with bones broken, sight or hearing impaired, minds unhinged. More people might have been killed or injured if it hadn't been the day of the pig market in Schiedam and of the fair in Voorburg, to which many had gone from Delft.    It was easier to determine damage to property. Anyone could see directly where whole streets had been blown away, where walls had fallen and roofs had collapsed. About two hundred houses were completely wrecked and about three hundred others needed major structural repairs. The Doelen -- the hall of the civic guard, named like the nearby inn after the targets on the archery butts the militia men shot at -- had been destroyed, and so had been the nearby quarantine hospital where plague victims were confined. On a smaller scale the blast had flattened the summer house, standing in an orchard, which had belonged to Burgomaster Bruin Jacobsz van der Dussen. Fortunately the seventy-year-old burgomaster, a member of a distinguished brewery-owning family (like many Delft patricians), was at the Town Hall at the time of the catastrophe; all his fruit trees were also blown down or shattered. On the churches, weathervanes were dented and twisted. Splits and cracks had appeared in walls everywhere. Because thousands of tiles had been torn from roofs, and many windows broken, the rain that fell for several succeeding days did further damage. Inside houses, precious objects had fallen from shelves, pictures had dropped from walls, and furniture was ruined. In many dwellings, like those of Fabritius and van der Poel, paintings were lost for ever.    Long-term assistance was gradually rendered. Some wealthy men bought thousands of roof-tiles and gave them out to the needy. The Provincial Council of Holland and West Friesland made a grant of 100,000 guilders to help pay for repairs. A tax holiday was allowed to those most severely affected -- for some, a period as long as twenty-five years free of property taxes was granted. Some victims received compensation, including six-year-old David Pieters, who had injuries that remained with him for the rest of his life; he was given a pension of twenty-five guilders a year. The list of claimants for building repair grants showed how the explosion was no respecter of occupation: it included people who were bakers, millers, shoemakers, harnessmakers, barrelmakers, glass-engravers, carpenters, turfcutters, silversmiths, painters, apothecaries, tobacco buyers, schoolmasters, wagon-builders, tile-bakers, and coffin-makers; even Simon Decker, verger and sexton, turned up in the lists, presumably as the result of a claim by his surviving family. Some claimants, among them Mathijs Pomij and Huych Leeuwenhoek, had several houses which they evidently rented out. Pieter Abramse Beedam, a coffin-maker in the Geerweg, put in for replacing 1,200 pan-tiles and 40 ridge-tiles at a cost of just over nineteen guilders. Widows and foreigners who owned Delft property made claims.    The dust had scarcely settled before some realised the tragedy might have its profitable side. There was of course a lot of work for builders and carpenters and glaziers -- fabers of all sorts -- and for the crews of barges which carried away rubble and brought in building materials. A new gunpowder store was built but was erected a mile from the city centre and well outside the city walls. Before the end of the year a journalist from Amsterdam named J.P. Schabaelje had produced a sensationalist pamphlet about the Donderslag , `the Thunderclap'. Two artists, Gerbrandt van den Eeckhout from Amsterdam, who had, like Fabritius, worked in Rembrandt's studio, and Herman Saftleven from Rotterdam, came to town to draw the wreckage. Van den Eeckhout's drawing showed the little girl in her high-chair being rescued and was used in the Schabaelje pamphlet. Local artists such as Daniel Vosmaer and the bereaved Egbert van der Poel began to make paintings of the scene, and, in the latter's case, to attempt to capture not just the after-effect but the very moment of the explosion. Van der Poel -- whether working through the pain of loss or simply working a market for disaster pictures -- painted the catastrophe over and over. Even though he moved to Rotterdam in 1655, it remained his subject; more than twenty pictures of the explosion by him still exist. Serious literary expressions about the tragedy were also published. Joost van den Vondel, the Amsterdam poet and playwright (and unofficial national laureate), composed a poem that recalled Delft's great fire of 1536 and invoked the power of Chaos: the gunpowder had been meant to be a support for the country, not its enemy, though it had buried Delft in a sea of ash. The chronicler Lieuwe van Aitzema eschewed Pompeiian metaphor but compared Delft to Jerusalem and Carthage; he said 100,000 cannons firing at the city couldn't have done more damage. Less helpful, at least to agnostic readers, were those commentators who viewed the ontploffing as a sign of the Almighty's wrath. The minister Petrus de Witte burst forth with a fiery pamphlet in which he explained that the explosion was a manifestation of God's displeasure at the mild, even tolerant way Delft Protestants had been treating other religious groups, rather than vehemently opposing them. The liberal Reformed, the Mennonites, and the Roman Catholics were just as much infidels as Mohammedans and other heathens. Indeed, Delft was a veritable Sodom or Gomorrah that deserved its fate. Petrus de Witte denounced the city council for allowing Catholic services to be held in the old Begijnhof chapel after the explosion. Similarly, if less obstreperously, a Jesuit priest, Arnout van Geluwe, said that he was taking comfort from the fact that neighbourhoods where `many devout Catholic hearts dwelt' had been spared -- a sure sign that God was looking after those He really cared for.    In front of the old Clarissen convent, when the rubble had been cleared, a large open space was made into a horse-market. The plague hospital was re-erected not far away, but this time outside the city walls on the east side of the Schie River. New houses were built in the wrecked streets. The Doelen of the Civic Guard and the Anatomy Chamber of the Surgeons' Guild were re-established on the Verwersdijk in a damaged building of the old St Mary Magdalen convent. Householders set to work to glue pottery and decorative tiles together and have damaged paintings restored. At the local Guild of St Luke, the crafts association to which Delft artists belonged, one of the headmen for that year pulled out a register and turned to the list of painters. He wrote after the name `Carolus fabrycyus', doot (`dead'). Fabritius had joined the guild two years before and was member number 75; the final instalment of six guilders he had owed for joining went unpaid, and so -- presumably -- did the 110 guilders he owed at the Doel tavern. Member no. 78 was a young Delft artist, ten years younger than Fabritius, named Johannes Vermeer, who had joined the guild at the end of 1653, the year before.    Fabritius and Vermeer had other links: paintings by the former turned up in the possession of the latter, paintings of the latter seem to show the influence of the former. Moreover, they both appeared in a 1667 guide to the city's history, topography, and most eminent personalities. The author, Dirck van Bleyswijck, a youth of seventeen in 1654, eventually became a burgomaster of Delft. In his Description of the City of Delft he described Fabritius as `an outstanding and excellent painter' and told of his death in the gunpowder explosion. And van Bleyswijck's publisher, Arnold Bon, who had his office and printing establishment in the Market Place and was also a poet, provided some dutiful but nevertheless poignant verses of his own on the death of `the greatest artist that Delft or even Holland had ever known'. These concluded: Thus did this Phoenix, to our loss, expire, In the midst and at the height of his powers, But happily there arose out of his fire Vermeer, who masterfully trod his path. A slightly different last stanza appeared in some copies of van Bleyswijck's Description , and the last two lines of this were But happily there arose out of his fire Vermeer, who proved to be as great a master.    One possible explanation for this small correction is that Johannes Vermeer walked the hundred yards or so from where he then lived on the Oude Langendijk to Bon's shop on the Market. He got him to pull the type and change a few words, making it evident -- if it wasn't so already -- that the younger man wasn't simply treading in Fabritius's footsteps but was able to paint as well as he and had succeeded him as Delft's leading painter. Copyright © 2001 Anthony Bailey. All rights reserved.