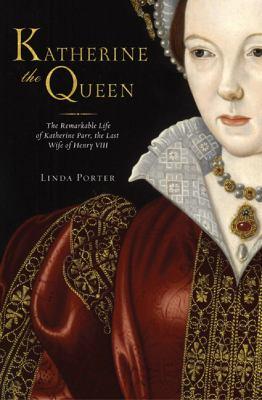

Katherine the queen : the remarkable life of Katherine Parr, the last wife of Henry VIII

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Victoria | Available |

Browse Related Items

- ISBN: 0312384386

- ISBN: 9780312384388

-

Physical Description

print

383 pages : illustrations (some color) - Edition 1st U.S. ed.

- Publisher New York : St. Martin's Press, 2010.

Content descriptions

| Bibliography, etc. Note: | Includes bibliographical references (pages 351-370) and index. |

| Immediate Source of Acquisition Note: | LSC 35.83 |

Additional Information

Katherine the Queen : The Remarkable Life of Katherine Parr, the Last Wife of Henry VIII

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

Katherine the Queen : The Remarkable Life of Katherine Parr, the Last Wife of Henry VIII

Chapter One The Courtiers of the White Rose 'The final end of a Courtier, where to all his good conditions and honest qualities tend, is to become an Instructor and Teacher of his Prince.' Baldassare Castiglione, The Book of the Courtier , 1528 Whitehall Palace is a long way from Westmoreland. In the sixteenth century the contrast between this opulent mansion on the busy river Thames and the wild country of the Lake District was even more pronounced. It took two weeks to travel between London and Kendal, the area's main town; a daunting prospect indeed and one seldom attempted in winter. Westmoreland was border country and its landowners and men of influence, often viewed as somewhat crude by their southern counterparts, were nevertheless expected to protect the king and the realm of England from the depredations of the country's neighbour, the violent, unpredictable kingdom of the Scots. But there was a lingering air of unreliability about the English nobility in this part of the kingdom. The Percy family's loyalty, in particular, was often in doubt, as was that of the other great northern clan, the Nevilles.1 The prospect of rebellion was never far away. And yet, even in this hostile environment, it was possible to prosper and to gain for one's family the prospect of influence and a better future. The family of Henry VIII's sixth wife had built their wealth, and thus their place in society, on the backs of the hardy sheep who grazed their lands on England's northern fringes. The famous Kendal Green wool produced by their flocks was much in demand and made them money. Though not of the aristocracy, service in the household of John of Gaunt and a marriage alliance with the prominent de Roos family enhanced their standing.2 Knighthoods followed and they began to hope for ennoblement, that most cherished of medieval social aspirations. In the late fourteenth century, they took their first steps on the path that promised advancement: they became courtiers and servants of the Crown. The Parr family motto, 'love with loyalty', seemed entirely apt. Over the next fifty years, the wealth of the Parrs grew. They acquired more lands and began to develop the complex web of local patronage and political presence that underpinned the fabric of rural England in the declining years of feudalism. But as the fifteenth century passed its midway point, with dissatisfaction growing against the inept rule of Henry VI, the Parrs had to consider exactly what 'loyalty' meant. In 1455, following the lead of the ambitious Nevilles, his powerful neighbours, Sir Thomas Parr, the head of the family, made a decision that had profound implications for his three sons. He would align himself with the party of Richard, duke of York, against the queen, Margaret of Anjou, and the clique of nobles who were manipulating the king and ruining the country. He did not know then what confusion, mayhem and sorrow lay ahead for the ruling class of his country, as it slipped into the troubled time known to history as the Wars of the Roses. Sir Thomas Parr fought alongside Richard Neville, earl of Warwick, and Warwick's father, the earl of Salisbury, at the battle of St Albans in 1455 and four years later at the battle of Ludlow. Here the Yorkists came off very much second best and Sir Thomas fled south, with the future Edward IV, and eventually took a ship from the Devon coast to France to await happier times. His action left him an attainted traitor, the future of his family very much in doubt. On his return, things at first went from bad to worse. He and his sons fought at the battle of Wakefield in December 1460, which saw the summary execution of the duke of York by the Lancastrians, led by the duke of Somerset. Sir Thomas himself was listed as dead but survived for another year. By that time, the pendulum had swung again and the Yorkists emerged victorious from the carnage of Towton in Yorkshire, on Palm Sunday, 1461. It was one of the bloodiest battles ever fought on English soil. When William Parr, the eldest son, assumed responsibility for the family's lands and future, there was no question that the Parrs were confirmed supporters of the White Rose. Nothing, however, was straightforward in those confusing times. As many of the old aristocracy perished in the convulsions of the next twenty-five years, so new opportunities arose for men who were willing to serve the monarchy in their stead. The Parrs were shrewd when they decided to divide their efforts. William stayed mostly in the north, managing the family estates and trying to combat the decline of law and order brought about by civil war and the continued menace of Scottish armies. He became, despite all the challenges, a very active local businessman, expanding his flocks, building new fulling mills to boost cloth production and, by the 1470s, controlling the net fishing industries of Windermere and other major sources of local food supply. His younger brothers, John and Thomas, meanwhile, went south to London, intent on establishing themselves at court. John became an esquire of the body in Edward IV's household and Thomas a retainer of Richard, duke of Gloucester. Yet the brothers were themselves to experience the tensions that ripped families apart during the Wars of the Roses. William was, unavoidably given his position in the north, Warwick's man. As the 'Kingmaker' grew into the fearsome overmighty subject who would challenge the young king himself, William Parr found himself on the opposite side from his siblings. The year 1470-1 has been described as one of the most confusing in English history. Opposed by the man who had helped put him on the throne, and by his own brother, the duke of Clarence, Edward IV fled to Burgundy, leaving his queen, Elizabeth Woodville, to take sanctuary in Westminster Abbey, where she gave birth to her first son. Edward was not exactly welcome in Burgundy - fugitive monarchs are always an embarrassment to their reluctant hosts - but he was determined that he would not stay there long. Henry VI was briefly restored, but the move smacked of desperation, for his sanity was clearly compromised. And despite the chaotic times, when shifting allegiances were commonplace, Warwick and Margaret of Anjou made strange allies. In reality, the earl had overstretched himself. His domination of English politics was at last broken on the battlefield of Barnet on Easter Sunday 1471, and he himself despatched by Edward's soldiers. William Parr had deserted Warwick by that time. In March, when Edward returned to reclaim his throne, the eldest Parr brother met him at Nottingham with 600 of his own men 'well arrayed and habled [prepared] for war'. It must have been a difficult decision to break with the Nevilles, and the anxiety that he might have miscalculated stayed with William Parr until Warwick was dead. That his gamble eventually paid off was no comfort for the loss of his youngest brother. Thomas Parr fell fighting beside the duke of Gloucester at Barnet. So the Parrs were not, in the end, immune to the sorrows experienced by many families in those unquiet days. Finally, on 4 May 1471, Edward IV inflicted a comprehensive defeat on Queen Margaret and her son at Tewkesbury. There was to be no sentiment for the vanquished. Henry VI may have been saintly but he was too dangerous as a figurehead to be kept alive any longer. His murder in the Tower swiftly followed the death at Tewkesbury of his only son.3 Edward had, at last, gained undisputed control of England. William and John Parr were with him at the climax of the Wars of the Roses. However much they mourned their brother and feared for their own survival, they did not waver in the end. The victorious king knighted John Parr on the battlefield. At last, the brothers would reap the full rewards offered by a grateful king. Recognition came quickly. Only weeks after Tewkesbury, Sir William Parr was appointed comptroller of the royal household, a key role in which essentially he managed all the king's personal expenditure. He also became a royal councillor. Sir John Parr was named master of the horse and constable of Kenilworth Castle. These were no mere decorative functions. The master of the horse controlled all the king's stables, horses, hounds and the paraphernalia that went with them. Both Parrs were given properties in the north that had belonged to the fallen earl of Warwick and John's position at Kenilworth, together with other grants of lands in Warwickshire, suggests that the king intended to build up a role for him in the heart of England. It was, however, in their frequent and physical proximity to the king that the Parrs enjoyed the greatest influence. They were typical of the kind of men, sound in outlook and loyalty, conscious of where they had come from and also where they hoped to go, whom Edward encouraged. He was suspicious of what remained of the old nobility and was under pressure from the tensions produced by the rivalries between his own brothers and the relatives of his wife, Elizabeth Woodville. The counsel and company of men he could trust and speak with freely were highly valued. These were true courtiers, not vainglorious aristocrats. And Edward, with his mixture of energy and laziness, his affability often masking a steely resolve when it came to his own survival, could not have been an easy man to serve. The year 1474 was perhaps the high point of Sir William Parr's life. He became a Knight of the Garter, one of only two members of the gentry to receive this honour in the second part of Edward IV's reign. By this time he held more than a dozen offices and had recouped the financial losses of the previous decade, when even his business acumen could not cover his mounting debts to the Crown.4 His successes enabled him to make an impressive second marriage in the same year that he received the Garter. On the death of his first wife, Joanna, William married Elizabeth Fitzhugh, niece of the late earl of Warwick and became, through her, a cousin to the king himself. William was forty by then and his new bride a mere twelve years old. A significant, though not quite so large, difference in age was to become a feature of Parr marital unions in the sixteenth century. Initially, the marriage was perhaps nothing more than in name. Elizabeth Parr did not give birth to her first child until she was sixteen years old. It was the dynastic alliance itself that mattered in such arrangements. Yet just one year after he wed Elizabeth, Sir William resigned from his role as comptroller and went back up to Westmoreland. This move may have been necessitated by the unexpected death of Sir John Parr, whose affairs required management. The elder Parr was with Edward IV in France for the campaign of the summer of 1475, but, that period apart, he did not return permanently to court and the personal service of the king again until the end of 1481. His reinstatement in the same office he had held before suggests that his stock had remained high with his royal master. In the six years of his absence, Sir William had worked mainly with Richard, duke of Gloucester, by now the king's only surviving brother.5 Gloucester had built up a power base in the north during his time as the visible presence of monarchy there and Sir William Parr was, effectively, his lieutenant. Parr's experience of dealing with the Scots was also important as relations between Edward IV and Scotland declined again in the last years of the king's reign. Whether Sir William was personally close to the duke, as his brother Thomas had been, is another matter. The unfolding of events in 1483 suggests that William Parr's loyalty was first and foremost to the Crown and to legitimate descent. Although the pursuit of pleasure had broadened Edward IV's girth and coarsened his youthful bloom, there is nothing to suggest that his health was giving rise to alarm. As late as Christmas 1482 he presided over sumptuous celebrations with his usual hedonistic enjoyment, in the company of his large family, 'frequently appearing clad in a great variety of most costly garments, of quite a different cut to those which had been usually seen hitherto in our kingdom', according to the Croyland chronicler. Ever conscious of his public image, Edward would have taken satisfaction in the comment that his dress gave him 'a new and distinguished air to beholders, he being a person of most elegant appearance, and remarkable beyond all others for the attractions of his person'. 6 Even allowing for some judicious flattery, this was clearly a monarch to be noticed and admired. So the sudden onset of serious illness in late March 1483 caused consternation. It may well be that Edward IV suffered a stroke. For eleven days after being stricken he lingered, alert enough mentally to try to reconcile his feuding relatives, aware as he must have been of the difficulties that would ensue for the minority of his son. But there was little doubt that he would not survive, and he died on 9 April, aged only forty. At his funeral, Parr was chosen to play the ceremonial role of man of arms: 'Sir William Parr, arrayed in full armour, save that his head was bare, and holding in his hand an axe, poll downward, rode up to the choir and, after alighting, was escorted into the church to make his offering as the man of arms'.7 It was Parr's last service to the king who had contributed so much to the rise of his family. The unexpected death of Edward IV plunged England into a deep political crisis that has been the stuff of drama, romance and divided opinion for more than five hundred years. The struggle for power that culminated in the disappearance of two young boys is one of the most fascinating in English history and the mystery that lies at its heart has never been solved. It remains an emotive issue to this day. But it is easy to overlook the impact that the events of the spring and summer of 1483 had on men like Sir William Parr, torn between conscience and expediency as they watched events unfold. In Parr's case, this led to a decision which could have caused a rift with his wife and her family. In the immediate aftermath of Edward's death it became apparent why, in the colourful language of the late fifteenth century, the collective term for a group of courtiers was a 'threat'.8 As his struggle with the Woodvilles and the queen became more bitter, the duke of Gloucester, nominated Protector of the Realm, had the full support of Sir William Parr. Lady Fitzhugh, Parr's mother-in-law, also put pressure on him to follow the duke's lead, perhaps because she and Elizabeth Parr were close to Gloucester's wife, Anne Neville, herself the daughter of Parr's old commander, the earl of Warwick. But these complex family networks were not, eventually, sufficient to persuade Parr that Gloucester's determination to gain the throne for himself was justified. The ruthless murder, on 13 June 1483, of William, Lord Hastings, one of the late king's closest friends and most trusted advisers, was the tipping point. Parr was loyal to the institution of monarchy but baulked at the idea of such a usurpation, however much it could be justified in terms of political expediency. He was wise enough to keep such thoughts to himself, though, and his attendance at the coronation of Richard III on 26 June was expected - indeed, he was listed as one of those who would carry a canopy during proceedings. But when the ceremony took place, he was absent. His womenfolk, however, were most definitely there, Lady Parr resplendent in the seven yards of cloth of gold and silk given 'by the King's special gift'. Her mother had been provided with material for two gowns, one of blue velvet and crimson satin as well as one of crimson velvet with white damask. It is not known which she wore as she rode behind Queen Anne, one of seven noble ladies given this honour. Elizabeth Parr was swiftly appointed as one of the queen's ladies-in-waiting, a further sign of royal favour. But while his wife seemed set to uphold the family's tradition of service in the new regime, Sir William Parr returned, for the last time, to Kendal. He personally wanted no part in King Richard III's regime. This does not mean that he and Elizabeth had fallen out; they may simply have felt it sensible for her to stay close to those in power, when he could not bring himself to do so. But it is not known whether she ever saw him again. He died in late autumn 1483, aged forty-nine, the last member of his family to reside in Kendal Castle. He had lived through a prolonged period of civil strife and still there seemed no permanent resolution of the dynastic problems that had beset England during his lifetime. He left behind four children, three sons and a daughter, the eldest of whom, his heir, Thomas, was five years old. When Richard III fell at Bosworth Field just two years later, in 1485, Lady Parr, still only twenty-three, faced a most uncertain future. Her destiny and that of her young family very much in her own hands, Elizabeth Parr demonstrated very quickly the capacity for balancing pragmatism with personal contentment that characterized her granddaughter sixty years later. She made a second marriage, some time early in the reign of Henry VII. It proved both happy and fruitful for her and gave her children by Parr a settled childhood, as well as improving their prospects in the uncertain landscape of the new Tudor England. Sir Nicholas Vaux of Harrowden in Northamptonshire, her second husband, was a member of an old Lancastrian family. His mother, a Frenchwoman, had been one of Margaret of Anjou's ladies and his father had died fighting for the queen at Tewkesbury. He had close links to the countess of Richmond, mother of Henry VII. In the new order, he cancelled out Elizabeth Parr's awkward Yorkist past perfectly. It was an inspired match. Thomas Parr and his siblings thrived in the congenial atmosphere of their extended family. Three daughters were born to Elizabeth and Nicholas, but no boys, and Thomas grew close to his stepfather. As the years went by, and Henry VII's hold on his throne, shaky at first, was tightened, Thomas was carefully educated and prepared to take his place at court. Nicholas Vaux had been brought up in the household of the king's mother, Margaret Beaufort, a woman of outstanding intellect and strong character, who was a notable patron of humanist scholars. The endowments she gave to Cambridge University, and St John's College in particular, helped develop the ideas of many of the leading intellectuals of the last two decades of Henry VIII's reign, men who would play a significant part in shaping religious reform and the education of Henry VIII's younger children. It has been suggested that Thomas Parr himself was placed in Margaret Beaufort's establishment at Colyweston, Northamptonshire, where other young gentlemen were sent to be educated by the Oxford scholar Maurice Westbury. Colyweston was close to Vaux's estates and his own connection with Margaret Beaufort during his childhood makes it entirely possible that he would have wanted his stepson to follow in his footsteps. Thomas Parr was given a classical education in Latin and Greek, and he also acquired all the polish and poise that would be required by a courtier. He may well have spoken French and other European languages, as was expected of gently-bred young men. All this would no doubt have pleased his father, though Sir William might have regretted his son's lack of interest in the steadily crumbling castle of Kendal itself. When he came into his inheritance in 1499, Thomas Parr was well aware that most of what his family had gained from their Yorkist connections had been taken back by the Crown. He would need to use his very considerable charm and courtly skills to stay close to those in power. But as the new century dawned he had reason to be optimistic. England was changing, and constant upheaval seemed to be a thing of the past. He could rebuild the family fortunes. And a first step on that road was to make, as both his parents had done, a good marriage. Fortune favoured Thomas Parr in his search for a suitable heiress. The opportunity that came his way was brought about by the death in the Tower of London in 1506 of Sir Thomas Green, a landowner from Northamptonshire whose curmudgeonly nature had led to charges of treason against Henry VII. The accusations may well have been unjustified. It was a time when disputes with neighbours were commonplace and frequently turned violent. Recourse to law to settle differences kept the legal profession busy. The blustering Sir Thomas had clearly miscalculated the effect of his aggressive behaviour and his health failed during his captivity. He left behind him two orphaned daughters, Anne and Matilda, heiresses to considerable wealth and an uncertain future. Within a year of her father's death, Thomas Parr purchased the wardship and marriage of the younger girl, fifteen-year-old Matilda, known as Maud. In 1508 he married her and, at about the same time, his stepfather Nicholas Vaux, by then himself a widower, married Maud's sister, Anne. This arrangement may appear calculated and no doubt it was, but it also brought happiness and security to the Green sisters, whose children grew up and were educated together in the close family relationship that Thomas Parr had enjoyed as a child. Through several generations, the intricate ties of their cousins and half-siblings would underpin the social standing of the Parr and Vaux families in Tudor England. Maud Green came from good Yorkist stock. Her maternal great-grandfather, Sir John Fogge, had been treasurer of the royal household between 1461 and 1468, in the first part of Edward IV's reign and would have known Thomas Parr's father, though it is unlikely they had been friends. Fogge was a Woodville henchman and liked to throw his weight around in a manner bordering on intimidation. On both sides, Maud's male forebears were an unpleasant lot. Yet she, happily, inherited the positive side of her father's attributes, all his confidence and passion and determination, without the tendency to make enemies. Thomas Parr must have known from the moment they met that her education and spirit, as well as her inheritance, were a good match for him. For despite Sir Thomas Green's inability to get on with his neighbours, he had not neglected the education of his daughters. Maud was fluent in French and probably read Latin as well. The age difference mattered much less than what she had in common with her husband. Certainly he did not treat her like a chattel and she no doubt appreciated the fact that this man twice her age, who had literally bought her, was refined enough not to rush her into the marriage bed before she had got used to him. It was clear that they would complement one another well. But their destiny depended on others. The key to their future together lay in Thomas Parr's careful cultivation of the teenage Prince Henry, the heir to the throne. The Parrs' situation was transformed by the death of the old king in April 1509. As part of Henry VIII's coronation honours, Thomas was created a Knight of the Bath. This social recognition no doubt pleased the new Lady Parr but, more crucially, it was soon followed by the waiving of some of the huge debt which had bound her husband (and many others of his background) to the Tudor dynasty. At the time of Henry VIII's accession, Thomas Parr owed the Crown almost £9,000, the equivalent of £4.5 million today. Much of this was for title to lands in Westmoreland, but part, of course, was for Maud herself. The king's generosity brought most welcome relief. Such actions may have endeared Henry VIII to his debtor lords, but his father, who had built a full Treasury on calling in these feudal rights, would not have approved. Henry VIII's relationship with his courtiers was all together different. They were companions and friends, only slightly less gorgeous than the handsome prince himself. He loved display and he wanted his court to reflect his youthful energy and love of magnificence. In this respect, he owed much to the flair and love of public show exhibited by his grandfather, Edward IV. The young king was determined to enjoy himself, to find outlets for his restive physicality and his love of music and composition. In these early days of the reign, during the summer progress of 1510, he passed his days 'shooting [archery], singing, dancing, wrestling, casting of the bar, playing at the recorders, flute, virginals, and in setting of songs, making of ballads, and did set two goodly masses, every of them of five parts, which were sung oftentimes in his chapel and afterwards in diverse other places. And when he came to Woking, there were kept both jousts and tournays. The rest of this progress was spent in hawking, hunting and shooting.'9 Henry's court was soon provided with that other prerequisite of the medieval ideal to which he aspired: a queen and her ladies. Katherine of Aragon married Henry in a private ceremony on 11 June. Their joint coronation followed on Midsummer's Day. The Spanish princess, marooned in England since the death of Henry's elder brother, Prince Arthur, some seven years earlier, now became the wife of the boy who had escorted her into St Paul's Cathedral on her first wedding day. This sounds romantic, but the truth was much less so. Katherine did not know the young king well and had been kept apart from him during the prolonged wrangling over her future between her own father, Ferdinand of Aragon, and Henry VII. There had been hard bargaining over the payment of the long overdue remainder of her marriage portion before vows were finally exchanged. She was nearly six years older than Henry VIII; not a huge difference, but he was barely eighteen when he ascended the throne and Katherine seems to have thought, with justification, that she knew more of the world than he did. She was never prepared to play the role of invisible queen consort, as Elizabeth of York, so briefly her mother-in-law, had done in the previous reign. But she was happy to wear the king's favours as he jousted, to worry over the injuries he sustained (which were to cause him great pain many years later) and to be his consort. Petite and golden-haired, she was an attractive young woman with an unmistakable air of regality. Katherine was the perfect foil to her husband's exuberance. Her contentment, with just a hint of indulgence, is apparent in the letter she wrote to her father, telling him that the days were passed 'in continual festival'. So these were good times for those families accustomed to serve. Both Sir Thomas and Lady Maud Parr were able to take full advantage of the openings for people of their background and social skills. They were often at court, participating in entertainments and disguisings, enjoying life to the full. Thomas and his younger brother, William Parr, were close companions of the king, part of the charmed circle surrounding the new monarch. They kept company with the Staffords and the Nevilles, the Carews and a diplomat-knight of Norfolk origin, Sir Thomas Boleyn. Amusement was constant, luxury unabashed. Henry had an innate grasp of the importance of image. The Venetian ambassador described his glittering appearance with awe: 'his fingers were one mass of jewelled rings and around his neck he wore a gold collar from which hung a diamond as big as a walnut'.10 The business of government he found irksome, but the possibilities of diversion were ever present. Typical of his rumbustious approach to life was his foray into the queen's chambers in Westminster one January morning in 1510, his entourage dressed as Robin Hood's men, bent on getting the ladies to dance. There was always about him something of the air of a practical joker (he used the same approach to impress a startled Anne of Cleves at their first meeting thirty years later, with such unfortunate results), but if the king's determination for such good cheer was occasionally oppressive, his companions knew better than to criticize. All seemed set fair for the Parrs. They preferred to follow the court rather than establish their residence in any one place. While her husband used his charm and courtier's training, Maud became a lady-in-waiting to Queen Katherine and served her faithfully for the rest of her life, from the heady early days of the reign through the testing time of the 1520s, until Maud's death in 1531. Theirs was a relationship that went much deeper than giddy pleasure. Both women knew what it was like to lose children in stillbirths and in infancy. During the first year of her marriage, Katherine had a late miscarriage, which pride and gynaecological ignorance refused to acknowledge. It began a pattern of failed pregnancies and infant deaths for which only the Princess Mary, born in 1516, was an exception. And Maud, too, suffered as many mothers did in those days. She conceived shortly after she married Thomas Parr and bore him a son. But any happiness at the arrival of an heir was fleeting; the child died young and not even his name is known. Then, between 1512 and 1515, three healthy children came in close succession. The eldest of these was a girl. She was christened Katherine, after the queen, who may also have been her godmother. The precise date of Katherine Parr's birth is not known but there is general agreement that it was probably some time in August 1512. The following year saw the arrival of her brother, William. Two years later a second daughter, Anne, was born. Despite their father's northern background, the Parrs grew up in the south of England. Kendal Castle was already falling into disrepair and it is not likely that Maud Parr would have struggled to the north of England for the birth. Her husband, though mindful of his family's origins in Westmoreland, never wanted to live there. It was too far from the centre of things. Nor does he seem to have desired to establish a pre-eminent residence among the properties he owned elsewhere. His base was very much London and the house he owned in Blackfriars, which was probably where Katherine was born. His reluctance to establish himself as a provincial grandee had nothing to do with monetary difficulties. At the beginning of 1512 he inherited half of the estates of his Fitzhugh cousin, Lord Fitzhugh of Ravenworth, making him a major landowner in the north-east of England as well as the north-west. Combined with the cancellation of the rest of his debt to the Crown the following year, Sir Thomas could be much more confident about his situation than he had been a mere four years earlier. But still no hereditary title came his way. Sir Thomas Parr accepted that, if he was ever to achieve this goal, he must continue to look for office and stay close to the royal family. Opportunities would present themselves, and he had a good eye for them. In 1515 he journeyed to Newcastle, ready to accompany the king's sister, Queen Margaret of Scotland, on her return to England. Margaret, who had a weakness for attractive men, seems to have been charmed by her gallant escort and stayed close to him throughout her month-long progress south to London. There was no hint of anything improper; Parr was merely demonstrating how perfectly he had mastered the courtier's arts. He knew, however, that acting the gallant to royal ladies was only part of the secret of success for a gentleman in his position. The following year he was offered a more prosaic but potentially lucrative role by his cousin Sir Thomas Lovell, a former chancellor of the exchequer. It was a new office - associate master of the wards - and Parr took it gratefully. Family connections thus helped to tie him to the growing civil service as well as the court. He also moved in the humanist, educated circles of his day and had a direct link to Thomas More, the renowned scholar and later Lord Chancellor. Thomas More's first wife was the daughter of Parr's stepbrother. Popularity, erudition and loyalty were important in the court milieu; but what he wanted, above all else, was to be Lord Parr and to pass the title on to his son. Thomas died without fulfilling his dream, at the age of thirty-nine, in the autumn of 1517. The onset of his illness appears to have been sudden and its outcome unavoidable, as he made his will only four days before his death. In it, he left marriage portions of £400 (£160,000) each to his two daughters, five-year-old Katherine and her little sister, Anne. This was not an overly generous amount and it suggests that he expected them to marry respectably rather than impressively. Maud, who was pregnant again at the time of his demise, was instructed that if she produced another daughter, the girl was to be married at her mother's expense. This seems a sour farewell to a woman who had been such a lively and committed helpmate, though it may reveal him as nothing more or less than a typical man of the early sixteenth century. His son, predictably, was left with much better provision, inheriting most of the estate. Still, he did nominate his wife as executor, along with Cuthbert Tunstall, the archdeacon of Chester (who was his kinsman), his brother, Sir William Parr of Horton, and Dr Melton, his household chaplain. He was buried close to his London home, at the church of St Anne's, Blackfriars. The inscription on his tomb read: 'Pray for the soul of Sir Thomas Parr, knight of the king's body, Henry the Eighth, master of his wards...and...sheriff...who deceased the 11th day of November in the 9th year of the reign of our said sovereign lord at London, in the Black Friars...'11 His will, with its mention of a signet ring given to him by the king, illustrates how close he was to Henry VIII. But this was only bleak comfort to Maud Parr, pregnant, grieving and left, at the age of twenty-five, a widow with three small children to bring up in a difficult world. KATHERINE THE QUEEN Copyright (c) 2010 by Linda Porter. Excerpted from Katherine the Queen: The Remarkable Life of Katherine Parr, the Last Wife of Henry VIII by Linda Porter All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.