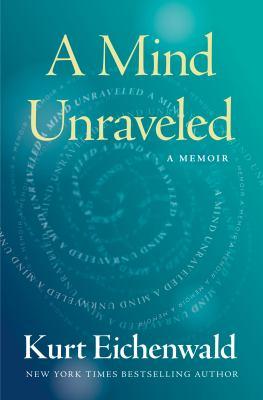

A mind unraveled : a memoir

The compelling story of an acclaimed journalist and New York Times bestselling author's ongoing struggle with epilepsy--his torturous decision to keep his condition a secret to avoid discrimination, and his ensuing decades-long battle to not only survive, but to thrive. Written with brutal and affecting honesty, Kurt Eichenwald, who was diagnosed with epilepsy as a teenager, details the abuses he faced while incapacitated post-seizure, the discrimination he fought that almost cost him his education and employment, and the darkest moments when he contemplated suicide as the only solution to ending his physical and emotional pain. He recounts how medical incompetence would have killed him but for the heroic actions of a brilliant neurologist and the friendship of two young men who assumed part of the burden of his struggle. Ultimately, Eichenwald's is an inspirational tale, showing how a young man facing his own mortality on a daily basis could rise from the depths of despair to the heights of unimagined success

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Victoria | Available |

Browse Related Items

| Subject |

| Eichenwald, Kurt, 1961- > Health. Epileptics > United States > Biography. Authors, American > Biography. |

| Genre |

| Autobiographies. |

- ISBN: 0399593624

- ISBN: 9780399593628

-

Physical Description

print

xiv, 402 pages - Edition Ballantine Books Trade Paperback Edition.

- Publisher New York : Ballantine Books, 2019.

- Copyright ©2018

Content descriptions

| General Note: | Cover image may differ. |

| Bibliography, etc. Note: | Includes Internet addresses. |

Additional Information