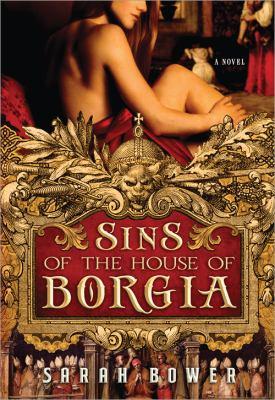

Sins of the House of Borgia

Violante isn't supposed to be here, in one of the grandest courts of Renaissance Italy. She isn't supposed to be a lady-in-waiting to the beautiful Lucrezia Borgia. But the same secretive politics that pushed Lucrezia's father to the Vatican have landed Violante deep in a lavish landscape of passion and ambition. Violante discovers a Lucrezia unknown to those who see only a scheming harlot, and all the whispers about her brother, Cesare Borgia, never revealed the soul of the man who dances close with Violante. But those who enter the House of Borgia are never quite the same when they leave--if they leave at all. Violante's place in history will test her heart and leave her the guardian of dangerous secrets she must carry to the grave.

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Victoria | Available |

Browse Related Items

| Subject |

| Borgia, Lucrezia, 1480-1519 > Fiction. Borgia, Cesare, 1476?-1507 > Fiction. Alexander VI, Pope, 1431-1503 > Fiction. Young women > Italy > Fiction. Household employees > Fiction. Nobility > Italy > Papal States > Fiction. Popes > Fiction. Italy > History > 1492-1559 > Fiction. |

| Genre |

| Historical fiction. |

- ISBN: 9781402259630

- ISBN: 1402259638

-

Physical Description

print

533 pages : geneological table, map ; 21 cm - Publisher Naperville, Ill. : Sourcebooks Landmark, [2011]

- Copyright ©2011

Additional Information

Excerpt

Sins of the House of Borgia

Chapter 1

Toledo, Omer 5252, which is the year of the Christians 1492

There are days when I believe I have given up hope of ever seeing you again, of ever being free, or master of my own fate. Then I find that the heart and guts keep their own stubborn vigil. When we say we have given up hope, all we are really doing is challenging Madam Fortune to prove us wrong.

When I was a little girl in the city of my birth, when my mother was still alive, she would take me to the synagogue, to sit behind the screen with the other women and girls and listen to the men sing the prayers for Shabbat. Sometimes, out of sight of the menfolk, while they were preoccupied by the solemnity of their duty, the women would not behave as their husbands and brothers and fathers liked to think. There would be giggling and whispering, shifting of seats, gossip exchanged by mouthing words and raising eyebrows. Fans would flutter, raising perfumed dust to dance in sunbeams fractured by the fine stone trellis which shielded us from the men. And around me was a continuous eddy of women, touching my hair and face, murmuring and sighing the way I have since heard people do before great works of art or wonders of nature.

This attention scared me, but when I looked to my mother for reassurance, she was always smiling. When I pressed myself to her side, fitting the round of my cheek into the curve of her waist, she too would stroke my hair as she received the compliments of the other women. Such a beautiful child, so fair, such fine bones. If I hadn't been there for her birth, added my Grand Aunt Sophia, I would say she was a changeling, possessed by a dybbuk. And several of the other children my age, the girls and little boys who had not yet had their bar mitzvah, would fix solemn, dark eyes on my blue ones as if, whatever Aunt Sophia said, I was indeed a dybbuk, a malign spirit, an outsider. Trouble. Rachel Abravanel used to pull my hair, winding it tight around her fingers and applying a steady pressure until I was forced to tip back my head as far as it would go to avoid crying out and drawing the attention of the men. Rachel never seemed to care that my hair bit into her flesh and cut off the blood to her finger ends; the reward of seeing me in pain made it worthwhile.

A year after the time I am thinking of, when Rachel had died on the ship crossing from Sardinia to Naples, Señora Abravanel told my mother, as she tried to cool her fever with a rag dipped in seawater, how much her daughter had loved me. Many years later still, I finally managed to unravel that puzzle, that strange compulsion we have to hurt the ones we love. As it was, from before the beginning of knowledge, I knew I was different, and in the month of Omer in the year 5252, which Christians call May, 1492, I became convinced I was to blame for the misfortunes of the Jews. It was a hot night and I could not sleep. My room overlooked the central courtyard of our house in Toledo, and, mingling with the song of water in the fountain, were the voices of my parents engaged in conversation.

"No!" my mother shouted suddenly, and the sound sent a cold trickle of fear through my body, like when Little Haim dropped ice down my back during the Purim feast. I do not think I had ever heard my mother shout before; even when we displeased her, her response was always cool and rational, as though she had anticipated just such an incidence of naughtiness and had already devised the most suitable punishment. Besides, it was not anger that gave her voice its stridency, but panic. "But Leah, be reasonable. With Esther, you can pass, stay here until I've found somewhere safe and can send for you."

"Forgive me, Haim, but I will not consider it. If we have to go, we go together, as a family. We take our chances as a family."

"The king and queen have given us three months, till Shavuot. Till then, we are under royal protection."

My mother gave a harsh laugh, quite uncharacteristic of her. "Then we can complete Passover before we go. How ironic."

"It is their Easter. It is a very holy time for them. Perhaps their majesties have a little conscience after all." I could hear the shrug in my father's voice. It was his business voice, the way he spoke when negotiating terms for loans with customers he hoped would be reliable, but for whom he set repayment terms which would minimise his risk.

"King Ferdinand's conscience does not extend beyond the worshippers of the false messiah as the Moors found out. For hundreds of years they pave roads, make water systems, light the streets, and he destroys them on a whim of his wife."

"And you would destroy us on a whim of yours? We have three months before the edict comes into force. I will go now, with the boys, and you and Esther will follow, before the three months is up, so you will be perfectly safe. Besides, I need you here to oversee the sale of all our property. Who else can I trust?"

"Here, then." I heard a scrape of wood on stone as my mother leapt up from her chair. I dared not move from my bed to look out of the window in case the beam of her rage should focus on me. "Here is your plate. I will fill it and take it to the beggars in the street. If you go, you will die."

"Leah, Leah." My father's conciliatory rumble. China smashing.

"Don't move. If you tread the marzipan into the tiles I will never get them clean." Then my mother burst into tears and the trickle of fear turned to a torrent of cold sweat, so when my nurse came in to see why I was crying, she thought I had a fever beginning and forced me to drink one of her foul tasting tisanes.

"I'm sorry, Haim," I heard my mother say before the infusion took effect and sent me to sleep. My father made no response and I heard nothing more but clothes rustling against each other and the small, wet sound of kissing that made me cover my ears with my pillow.

A week later, my father and my three brothers, Eli, Simeon, and Little Haim, together with several other men from our community, left Toledo to make the journey to Italy, where many of the rulers of that land's multitude of tyrannies and city states were known to tolerate the Jews and to be wary of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, whose approach to statecraft was not pragmatic enough for them. Even the Kingdom of Naples, which was ruled by relatives of the king, was said to be content to receive refugees from among the exiles of Jerusalem. My father, however, intended to go to Rome. The pope is dying, he explained, and there is a Spanish cardinal prepared to spend a lot of money to buy the office when the time comes. This Cardinal Borja will be needing a reliable banker. We were unsure what a pope was, or a cardinal, and Borja sounded more like a Catalan name than a Spanish one to us, and a Catalan is as trustworthy as a gypsy, but my father's smile was so confident, his teeth so brilliant amid the black brush of his beard, that we had no option but to nod our agreement, bite back our tears, and tell him we would see him in Rome.

Excerpted from Sins of the House of Borgia by Sarah Bower All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.