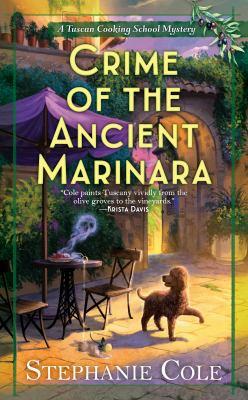

Crime of the ancient marinara

Hoping for a fresh start in Tuscany, Italy, farm-to-table cooking school owner Nell Valenti finds her new business in danger when a visitor is poisoned by the top secret marina recipe of a famous chef.

Browse Related Items

| Subject |

| Women cooks > Fiction. Americans > Italy > Fiction. Cooking schools > Fiction. Murder > Investigation > Fiction. Tuscany (Italy) > Fiction. |

| Genre |

| Detective and mystery fiction. Cozy mysteries. |

- ISBN: 9780593097816

-

Physical Description

print

290 pages. ; 18 cm. - Edition First edition.

- Publisher [Place of publication not identified] : [publisher not identified], 2021.

Content descriptions

| General Note: | Recipe included. |

Series

Additional Information

Crime of the Ancient Marinara

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

Crime of the Ancient Marinara

1 Five o'clock Early October There were six of us assembled for final preparations in the common room of the Villa Orlandini on a hillside just outside of Cortona, Italy. The villa was home to Chef Claudio Orlandini, his Cornell-educated olive-growing son, Pete, and an assortment of helpful women of the Bari family-not the least of which was the redoubtable Annamaria, the sixty-ish sous-chef who had been keeping the Orlandini household humming along for decades. Not quite a month ago, I, Nell Valenti, had been transatlanticly wooed by a lawyer representing the Orlandinis to come to Cortona, Italy, and develop a world-class cooking school at their villa. Five hundred years ago the property was home to the order of St. Veronica of the Veil, but that was back in the day when the joint was a run-down convent and not the fine, run-down villa it was today. And now, I thought, here we were, on the eve, on the brink, very possibly even on the ledge, for all I knew. Chef, Pete, Annamaria, Rosa, Sofia, and I. Chef dubbed the theme for our first "intensive" Marinara Misteriosa. This culinary virtuoso had found himself longing for the days of his explosive rocketing onto the culinary world stage back in his twenties when his own secret marinara recipe was introduced to Italian sauce lovers the world over, who instantly proclaimed it the finest advancement in marinara development in the last two hundred years. Love, fame, and money followed. But now? I had my doubts. How many people, I argued, are going to spring for round-trip airfare plus our fees, not to mention clear their own schedules at short notice, for four days at the villa to learn something they could probably figure out at home just by popping the lid on a jar of Newman's Own? The answer came within days of launching the website: five. Five Americans signed up. When I announced to Chef, the Baris, and Pete that Marinara Misteriosa was a go, Chef kissed both my cheeks. And now here we were, meandering around the common room with our hands in our pockets, taking care of last-minute tasks, eyeballing the beautiful changes to the space, on the afternoon before the five Americans showed up who were paying top dollar to be in the presence of the first real celebrity chef-well, from Tuscany, under two hundred pounds, and born less than five years after the death of Mussolini. To make my life a little easier, I decided to go with Cucinavan, owned and operated out of Florence by Manny Manfredi, whose gastrotour services would include handling the money, coordinating airport pickups and drop-offs, transportation to and from the villa-and whatever foodie hot spots and shrines he could offer to our students along the way. At two p.m. the next day, Cucinavan was arriving from Florence with our first class of American gastrotourists. Four days, five students, learning at the sauce-stained knees of renowned chef Claudio Orlandini-how hard could it be? And if we hit a few snags, as Chef himself would say, Tutto fa brodo-Everything makes broth. The first time I heard Chef use the common Italian phrase, I knew we had our brand, and it gave me a little frisson of pleasure. Everything makes broth. Three weeks ago, that outside wall had been stripped of its peeling wallpaper, washed, dried, and painted a bright teal in chalkboard paint. I found a sign painter in Siena who did the lettering in gold leaf centered high up on the gorgeous teal wall: TUTTO FA BRODO, with plenty of slants and serifs to make the Orlandini Cooking School brand glisten with all the agelessness of a fresco. I crossed my arms, amazed at the changes. No more muschio, the moss that had been providing the 3-D effect on the moist walls. No more mildew. Luscious rugs in geometric whites and golds offset the wall hanging, stainless steel worktables doubling as desks glinted in the daylight, and Bauhaus metal and sling-back leather chairs outdid anything I ever owned, that was for sure. For a moment, my heart picked up a beat, and I thought the Villa Orlandini Cooking School might really stand a chance. Today, down at the far end of the wall, near where the American foodies would put up their throbbing feet at the end of a tough day with polenta, Rosa and Sofia, Annamaria's sisters who were members of the order of St. Veronica of the Veil, were fifteen feet off the ground on rickety ladders, hanging a ten-by-twelve-foot tapestry banner in a famous William Morris Oriental design. Clustered below, shouting directions, and gesturing as broadly as a traffic cop, was Annamaria. More this way, more that way, higher, lower, are you drunk? When we all finally agreed that the banner was as straight as we could get it without either a carpenter's level or an infusion of tea, we flopped into chairs and waited for Annamaria to wheel in her tea cart with extravagant antipasti aboard. Nibbling on a peperoncino, the stalwart Rosa thumbed the remote and navigated her way to a cable TV channel, then upped the volume as though she had a twitch, and we all stared at Rosa's daily fix of a close-captioned American show called Stealth Chef. "Ecco Stealth!" she stage-whispered as though drawing our attention to a shadowy image of the Blessed Virgin on the side of an Arkansas barn. Stealth Chef-face obscured by a black bandana, hair obscured by a professional black head wrap, voice distorted by a high-tech voice changer-had hit on a gimmick that was sheer kitsch. But it worked, and it sold, and it topped late afternoon cable culinary shows. I had to admit, Chef Orlandini's merry little Tutto Fa Brodo brand looked a little ho-hum alongside Stealth Chef's brand, splayed across the simple set kitchen: Recipes for All. This anonymous dicer slicer, filming from an undisclosed location in the United States, was dubbed the Robin Hood of celebrity chefs. While waiting for the pasta pot to boil, the disguised voice lost no opportunity to plug the shtick: "Recipes belong to everyone," the figure mincing garlic intoned sincerely, "nothing hidden, nothing withheld, the democracy of a world kitchen, where rich and poor share and share alike." You would swear Stealth Chef was about to break into doomed and righteous song at the barricades in Les Mis. All the PC words got gonged: democracy, rich, poor, world, share. The result in the year Stealth Chef had been on the air was a ratings top spot as unassailable as my own Chef Claudio Orlandini's five-tier tiramis. But everyone loved Stealthy's mystique. The bandana, the head wrap, the voice changer-pure theater. The problem with all this televised celebrity was that it started to give Rosa Bari ideas. Would Chef consider a gold hoop earring? A fish tattoo? A paisley ascot? A nose job? Thankfully, she voiced these abominations only to Pete or to me, on some level knowing better than to make any direct suggestions to Annamaria or Chef himself. The two times Chef wandered through the common room when Stealth Chef was on the air, he truly stopped dead in his tracks, transfixed as though he had spotted the East African oryx on the Serengeti Plain. He seemed okay with the disguises-after all, Chef's easy charm was probably in the same league as Stealth Chef's bandana-but his eyes widened in shock when the whole concept of Recipes for All got plugged. You would think he was watching either an autopsy or a student with bad knife skills. Right there in front of him. "Cosa sta dicendo?" he declared: What is he saying? Then, hoarsely: "Ricette per tutti?" Recipes for all? He was baffled. With arms open wide, Chef Claudio Orlandini turned slowly, addressing the walls in broken English. Where, then, is the art? The pricelessness? Palming a few cubes of fresh mozzarella from the antipasto tray, plus two slender breadsticks, I motioned to Rosa and Sofia to turn off the TV. Sofia, who was in charge of the remote at that moment in time, clicked it once, and both of them headed like long-suffering galley slaves toward the classroom stainless steel tables. We all sat. Pete dashed in and scraped over a chair he flipped around and straddled. Chef's only son was forty, with short dark hair, hazel eyes, and angular cheekbones. He loved his father without losing sight of the man's shortcomings, and he became my friend one night over dinner, at a time when a murder too close to home nearly derailed all of us. Over the past weeks, I had been developing both a start-up cooking school and a fondness for this man who could turn a beautiful black Moraiolo olive between his fingers and gaze at it like it had a story and the value of a diamond. Annamaria, dressed in an elegant navy blue sheath, dropped straight-backed onto a bench and folded her hands prayerfully. A former nun herself, Annamaria slid in and out of this default position. We smiled and tipped our heads at each other as if we were meeting after a very long time away. At length, she began to pour tea. Sofia passed a plate of rolled and speared anchovies. Pete popped a couple of olives. Rosa appeared to be daydreaming. I had six sets of photocopied information collated and stapled. These I passed out in a silent rustle, setting Chef's next to me until he returned from the bocciodromo, the indoor bocce dome, and joined us. He never fretted, sensing, I'm pretty convinced, that when I showed up last month fretting was penciled into my job description. "I nostri studenti domani." In my half-baked Italian, I drew their attention to the top sheet. Manny Manfredi of Cucinavan had sent me a nice printout of the Americans who had signed up-not to mention paid up-for Marinara Misteriosa. Alongside each alphabetized name was age, permanent address, and occupation. I went down the list. Jenna Bond, 24, Baltimore, MD, barista, Artifact Coffee Zoe Campion, 34, Chatham, NJ, outdoor educator, Walden Trails School Glynis Gramm, 53, Naples, FL, owner, Gulf Coast Apparel Robert Gramm, 54, Naples, FL, owner, Gramm's Lams dealership George Johnson, 37, Brooklyn, NY, server, Fra"che Take Bistro Annamaria perused the list with a scowl, then swatted it lightly with the back of her hand. "Only one, how you say, cook." I turned to her. "Which one?" All three Bari sisters answered at once with many shrugs. "Giorgio." I looked at the entry for George Johnson, not seeing what to them as they sat with folded hands was obvious. "Why do you say that?" At their blank looks, I tried again. "PerchZ?" As she fussed at the clip that held back one side of her salt-and-pepper hair, Annamaria blinked at the ceiling. "Bistro." Sofia and Rosa nodded vigorously at their elder sister's sagacity. I held up a finger, not my first choice. "Actually"-I raised my voice, quickly muttering out of the side of my mouth to Pete, "Jump in, okay?"-"all we know about Giorgio is that he's a waiter-cameriere, capisce?-which doesn't mean he cooks." This brilliant deduction was met with appreciative murmurs from my colleagues. I went on. "Judging by the scant information we have on our first group of students, we can't make any inferences about who comes to us with cooking skills and who does not." Three faces turned in unison to Pete, whose melodious Italian translated my point. I sipped my tea. Then I launched into what I always think of as my Battle Stations speech, developed over my lengthy career of designing cooking schools (four, total, including this Orlandini gig), and which I'd distilled down to three rules. For these, I pushed back my chair and stood at my place. "Uno," I bleated. "Assume no kitchen skills. They are here to learn, so, we will teach them. Whether they're good or they're bad, show no shock. We work with what we've got." I inhaled and delivered the most craven part of the Battle Stations speech. "Insofar as we can"-I scanned their intense faces-"we give them some tips, we give them some recipes, some wine, time in the presence of our celebrity chef, and we send them off happy. We are selling the Orlandini Cooking School experience." Their faces hadn't changed. "Due," I went on, regarding the ceiling. "No fraternizing." In Italian, Pete went on a little long on this point, I thought, ruling out lovers, pals, drinking buddies, dance partners, roommates, and piano accompanists. At that one, I eyed him. He studied a stunted olive. Then I grabbed the list of names and waved it around. "These are our customers. Do you understand?" "Our students," amended Annamaria, trying for the high road. I think she was privately savoring an image of these five Americans as holy seekers. Had she not been listening to Rule #1? I pressed my lips together. "Our customers," I repeated. "We will be living here in close quarters"-Pete was all over this half sentence like shine on polyester; Rosa made a cat call-"so we behave with the utmost professionalism at all times." "No hello?" "Of course hello. Be cordial and helpful at all times." When I saw how wide their eyes were with this, well, loophole, I fretted. All I could throw on top of Rule #2 was something about thinking of these five American gastrotourists as shoppers who have entered our retail establishment. We want to sell them our goods, but we want to respect their space. Pete apparently thought it advisable at this point to encourage some role-playing, because before my very eyes, Rosa and Sofia moved quickly away from the table. Wringing her hands, Rosa smiled dementedly at Sofia. "I show you a, how you say, sautZ pot-" "Pan." Annamaria scrutinized her fingernails, as though she had been saying "pan" all of her sixty years. "Yes," murmured Sofia, flushed with competence, "you do." Keeping the kind of distance from her customer I recalled from the leper colony scene in Ben-Hur, Rosa waved her all the way out of the common room, then turned and curtsied. We all clapped, and clapped again when Sofia skipped back in and took a bow. I debated finessing the performance, but decided against it, finally. They got the basics just fine-sell them on the Orlandini experience, but respect their space. Pete said, "What's next?" I nodded at him and sang out "Tre." Speared anchovies, cubed cheeses, stemmed peperoncini paused in midair. I had their attention. "Refer all suggestions and complaints to-" For a nanosecond of horror, I realized I hadn't worked out this point. Who was the go-to for the program? Not Chef, not unless it had something to do with asking him whether the dough was stretchy enough. Not Annamaria, although I considered her-she was, after all, inner circle, but even after our short acquaintance I knew this woman's realm was the kitchen, at Chef's side, and she was stunningly single-minded. Not Pete, although he handled the villa accounts, so had a finger on the business side of things. Still, he was chin deep in the olive harvest and could only be called on occasionally as an instructor, depending. Excerpted from Crime of the Ancient Marinara by Stephanie Cole All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.