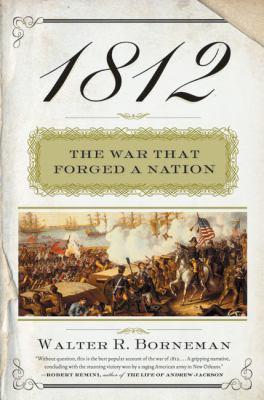

1812 : the war that forged a nation

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Victoria | Available |

Browse Related Items

| Subject |

| United States > History > War of 1812. United States > History > War of 1812 > Influence. |

- ISBN: 0060531126

-

Physical Description

print

xii, 349 pages : illustrations, maps - Edition 1st ed.

- Publisher New York : HarperCollins, [2004]

- Copyright ©2004

Content descriptions

| Bibliography, etc. Note: | Includes bibliographical references (pages 305-333) and index. |

| Immediate Source of Acquisition Note: | LSC 36.95 |

Additional Information

1812 : The War That Forged a Nation

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

1812 : The War That Forged a Nation

1812 The War That Forged a Nation To Steal an Empire In the early twilight, the swollen waters of the Ohio River swept a wooden flatboat up to a landing on a small, tree-covered island. On the river's east bank lay the western reaches of the state of Virginia; on the west, the shores of the state of Ohio, now, in the spring of 1805, barely two years old. The flatboat was much grander than the normal river craft that floated by or landed here. Indeed, its owner had commissioned its recent construction in Pittsburgh, and he himself described it as a "floating house, sixty feet by fourteen, containing dining room, kitchen with fireplace, and two bedrooms, roofed from stem to stern ... " The flatboat belonged to Aaron Burr. With jet-black eyes, a silken tongue, and the refined dress to match the accoutrements of his vessel, Burr cast a larger shadow than his diminutive height suggested. For four years, he had been the proverbial heartbeat away from the presidency, but once he had also been just one particular heartbeat away. Why the recent vice president of the United States came to make this journey down the Ohio River evidences just how tenuous the American union still was in 1805, and that the very last thing it should have come to contemplate was another war with Great Britain. In the presidential election of 1800, there were as yet no strictly organized political tickets. Prior to the Twelfth Amendment, the Constitution merely ordained that the person receiving the highest number of electoral votes be declared president and the second highest, vice president. Party electors were supposed to withhold a vote or two from the agreed-upon vice presidential candidate, thus assuring the election of their presidential favorite. Such informality didn't work very well. In fact, so many Federalist electors withheld votes from John Adams's running mate in 1796 that Republican Thomas Jefferson ended up with the second highest number of votes and the vice presidency. (Jefferson's Republicans were the liberal predecessors of the Jefferson-Jackson Democrats and not the "Grand Old Party" of Abraham Lincoln.) To avoid such a result in 1800, Republican vice presidential candidate Aaron Burr obtained Jefferson's assurance that no southern elector would drop a vote for Burr, but that Burr would arrange for a Republican elector from Rhode Island -- supposedly a solid Jefferson state -- to withhold one vote for Burr. That strategy backfired when the Federalists proceeded to win Rhode Island, and the remaining Republican electors cast the identical number of votes for president and vice president. Thus in only the nation's fourth presidential election, Thomas Jefferson handily defeated incumbent John Adams, but imagine Jefferson's surprise when his vice presidential running mate received the same number of electoral votes as he, and the election was declared a tie. With Jefferson and Burr each receiving seventy-three votes, the election went to the House of Representatives, where the contest was suddenly not between Federalist and Republican, but between Republican and Republican. Vice presidential candidate Burr professed allegiance to Jefferson, but made no outright disclaimer of the higher office. Indeed, there were plenty of whispers in Burr's ear to suggest that the higher office was his for the taking. New England Federalists, who were rarely as unified in anything as they were in their opposition to Thomas Jefferson, actively courted Burr, vastly preferring the New York lawyer -- Republican though he might be -- to the Virginia planter. Not all Federalists felt that way, of course. Alexander Hamilton for one was appalled at the possibility of Burr becoming president. Four years before he would die by Burr's dueling pistol, Hamilton wrote: "There is no doubt but that upon every virtuous and prudent calculation Jefferson is to be preferred. He is by far not so dangerous a man and he has pretensions to character." Among other things, Hamilton probably feared that Burr might come to take over the Federalist Party that Hamilton clearly viewed as his own exclusive route to the presidency. In the House of Representatives, the Federalists controlled six states, the Republicans eight. Two states were undecided. A simple majority of nine was needed to elect either Jefferson or Burr president. For a turbulent six weeks, the electoral balloting and the intraparty intrigue continued. Certain Federalists and Republicans friendly to Burr clung to the hope that they might be able to swing three states into the Federalist column and make Burr president. Finally, after some backroom concessions obtained from Jefferson through Alexander Hamilton, James A. Bayard of Delaware -- the undecided state's lone vote in the House of Representatives -- voted for Jefferson to give him the required nine states. Aaron Burr would spend four years being a heartbeat away from the presidency, but he lost it by the single heartbeat of James Bayard. Both Jefferson and Burr were quick to say that each bore no hard feelings toward the other, but more than a few Republicans noted how far Burr had been tempted to stray to the Federalists, and, likewise, the Federalists knew how close they had come to getting him. The result was that both sides came to view Burr as something of a leaf willing to be blown by whatever political winds offered the promise of greater glory. For Jefferson's part, he would soon prove that he hadn't meant that line about "no hard feelings" after all. So Aaron Burr became vice president of the United States in March 1801. By most accounts he served a distinguished term, taking seriously his charge to preside over the United States Senate and tarnishing his reputation only through his duel with Alexander Hamilton. Even by the standards of 1804, it is difficult to grasp that a sitting vice president of the United States should fight a duel, let alone kill his opponent, but in truth Thomas Jefferson had been determined to rid himself of Burr long before the public uproar over the duel. 1812 The War That Forged a Nation . Copyright © by Walter Borneman. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers, Inc. All rights reserved. Available now wherever books are sold. Excerpted from 1812: The War That Forged a Nation by Walter R. Borneman All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.