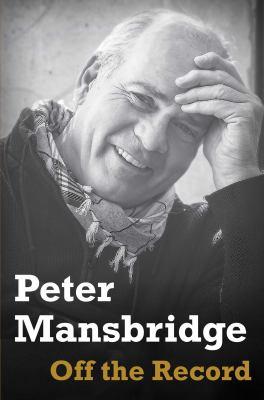

Off the record

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Community Centre | Available |

| Victoria | Available |

Browse Related Items

- ISBN: 9781982169602

- Physical Description x, 354 pages : illustrations (some color) ; 25 cm

- Edition Simon & Schuster Canada edition.

- Publisher [Place of publication not identified] : [publisher not identified], 2021.

Additional Information

Off the Record

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

Off the Record

Beginnings Beginnings As the story goes, Julia Turner was just sixteen years old when she crossed Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood to go for a Coke in a soda shop on the other side of the street. Inside she was spotted by a reporter, who introduced her to an agent, who changed her name to Lana, and the next thing you knew she was a big star, a leading lady in the movies. Well, I wasn't sixteen, I was nineteen, and I wasn't in Hollywood, I was in Churchill, Manitoba. But after that, there are, as strange as it seems, some similarities to our stories. I was a high school dropout, fresh from a short, unsuccessful stint in the Canadian navy, who moved west in 1968 looking for a new start. I found work as a baggage handler slash ticket agent for a little regional airline called Transair. How I got the job is a story I'll tell later. As I said, I was looking for a "new start," and tossing bags was certainly that. Transair trained me in Winnipeg, then sent me first to Brandon, Manitoba, and then to Prince Albert, Saskatchewan. I'd only been in PA a month or so when they decided to close down the station. They told me I was going to Churchill to fill in for a guy who was on two weeks' holiday. I got there. He never came back. And I didn't leave. Which leads me to the day I was asked to announce a flight departure on the little public-address system. The PA system was set up on a podium right in the middle of the waiting room, which was filled with anxious passengers ready to board the daily Transair DC-4 flight to Winnipeg. I clicked down on the microphone button: "Transair Flight 106 for Thompson, The Pas, and Winnipeg is now ready for boarding at Gate One." We only had one gate, but it sure sounded like something you'd hear the big airlines say. "Passengers travelling with children or those requiring boarding assistance, please see the agent at Gate One." As passengers started moving toward the gate, one person came in the opposite direction. Toward me. "You have a really good voice," the man said. "Have you ever thought of being in radio?" His name was Gaston Charpentier and he introduced himself as the manager of the CBC Northern Service Radio Station, CHFC, just down the road in Fort Churchill. And that's when opportunity knocked. My "Julia Turner" moment. No experience. No background in the business. Turner had the looks, I had the voice. Charpentier explained how the station was looking for a late-night announcer who could host a two-hour music show between 11 p.m. and 1 a.m. and then sign the station off the air for the night. He said he couldn't find anyone in town who was interested and asked whether I was. No audition. No HR interview. Part-time job for the asking. I grabbed it. It meant more money, as I was only making $225 a month at Transair. And it sounded a little more interesting than "baggage handler." Charpentier said I could start the next night. After completing my regular day shift at Transair, I went over to CHFC to learn the ropes. One of the regulars, a fellow from Calgary by the name of Bill Gray, gave me the rundown. We started in the record library, which in those days was a set of long bookcases with hundreds and hundreds of 45s, and dozens and dozens of LPs. Bill showed me how the cataloguing system worked and then we moved into the studio for the real training session. CHFC was basically a one-person operation. During the early morning and late-night slots, the only person there was the on-call "announcer," so that person had to do everything. Cueing up records wasn't that hard, though there was a knack to it that had to be mastered. Same with the microphone. But this wasn't rocket science and if I could calculate the weight balance of a fully loaded DC-4 ready for its run to Winnipeg, I was pretty sure I could cue up a record. By the time I left the station, I was feeling comfortable about the next night when I'd be on my own for my debut. The graveyard shift, as it was, actually ran from roughly eight thirty in the evening until signoff just after one a.m. I said good night to the announcer going off duty at eight thirty and was the only person left in the station. CHFC aired the CBC Radio network feed from Winnipeg for most of the evening, so my duties were minimal until the record show "Nightbeat" would start at eleven p.m. My first on-air moment was a thirty-five-second station break at 8:59:25. At that time, I would click open the microphone and confidently say the station identification and give the local weather report. "This is CHFC Fort Churchill where the current weather shows a temperature of (whatever) with the winds from the (whatever). The wind chill factor is (whatever). Next on our schedule is (whatever)." Those words were all typed out on a piece of paper and I just had to fill in the blanks. Easy peasy, right? Nope. Not that night. I practiced the script--with the blanks filled in--over and over. But at about 8:50, the network line from Winnipeg suddenly went dead in the middle of their programming. Nothing, not even a hum. I was in shock. No one had briefed me on what to do with a situation like that. So, I had to draw on my memory as a youngster in the 1950s listening to the CBC at home with my parents, where things like that happened somewhat frequently. I reached for the microphone switch, leaned toward the mic. And then uttered the first words I would ever say on the CBC: "One moment, please." And then I switched off the mic and wondered what I would do next. Five seconds went by, then ten. I was about to really panic when, just as quickly as the feed had disappeared, it came back on and everything returned to normal. The rest of my debut evening went fairly well. I was nervous and probably said some dumb ad-lib music things between records on "Nightbeat," but no one complained. I'm not even sure if anyone was listening, but by the time I left the building I felt pretty good. Over the next few months, however, I quickly realized that if I was going to make broadcasting a full-time career, it wasn't going to involve music. It just wasn't my thing. Even back in my high school music class, the teachers could tell that I didn't, and wasn't going to, "get it." They started me on the trumpet but I couldn't hit the high notes, or in fact, any notes. Then the trombone. Finally the tuba. Nothing worked. At CHFC, each week new records would arrive from the record companies. We'd sit around and rate the chances for each record. I remember the day Simon & Garfunkel's song "Bridge Over Troubled Water" arrived. It was so long, I said. Boring. It'll never make the charts. Bill Gray just shook his head. As I said, music just wasn't my thing. But I knew what was. News and current affairs. Ever since I was a child, I had been fascinated by the news of the day, whatever that news was. Along with history, current affairs was, as a result, my favourite topic. So, in 1969, shortly after being offered a full-time job at CHFC, I suggested moving off "Nightbeat" and starting a daily newscast, which at the time the station did not have. They agreed and "The News with Peter Mansbridge" was born. In the beginning, it was only a few minutes long, each evening at 5:30. I'd talk to the RCMP, the town office, the Port of Churchill, and the National Research Council, which operated the Churchill Rocket Range. Between them, there was always something to discuss on air. And then, of course, the polar bears. You couldn't miss with a story on the bears. But I needed more than content to do a newscast. I needed to know how to write, to interview, to edit, to line up, and to do all the other things real newscasters and producers did. But there was no one to teach me. I was all alone. So, each night, I would listen to the CBC newscasts from Toronto and Winnipeg, and to shortwave radio--the BBC, the Voice of America, and, when I could tune them in, the big radio networks in the United States like CBS, NBC, and ABC--eagerly devouring how others did what they did. I didn't copy, I learned, and soon "The News with Peter Mansbridge" expanded to thirty minutes and included interviews often done on location on a big, heavy, Nagra tape recorder that I lugged around town and then edited back in my office. The only known picture of me at the CBC in Fort Churchill, Manitoba, circa 1969. University of Toronto Archives I even started an open-line radio show in the mornings, called "Words with Peter Mansbridge." It was a big deal for a little town of less than two thousand where most everyone knew everyone, so there was no anonymity if you were suddenly "on the air." That first day was interesting. I opened the program with some nice theme music and welcomed the audience to the new age of broadcasting: we were going to be just like the big cities down south. I asked them to call in and share their thoughts on the topic of the day and then waited for the lines to light up. Nothing. The show was thirty minutes long and no one called. Not one. Not even a wrong number. I talked for thirty minutes nonstop. By the end, I was almost begging. By day two, the show was called "Words and Music with Peter Mansbridge." Over time the callers started dialling in, and that program and the daily news picked up a good audience. I began making a name for myself in both Winnipeg and Toronto because I would offer cut-down versions of my stories for their newscasts. They were almost always human-interest stories dealing with living in the north, or they were about polar bears. A polar bear story was a ticket to network exposure. And then in late 1970, Herb Nixon, one of the most powerful names in CBC News at the time, called me up and said, "Peter, we'd like you to apply for an opening we have here in the Winnipeg newsroom." But there were more Churchill adventures to come first. Excerpted from Off the Record by Peter Mansbridge All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.